10 years of the REAL Centre

Tackling injustices in and through education.

Ten years ago, the University of Cambridge launched a new research centre with a striking ambition: to tackle some of the deepest inequalities in global education. Reflecting a growing research strength at the University and based in its Faculty of Education, the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre was created not just to understand more about the barriers to education experienced by millions of young people, but to provide rigorous evidence and clear policy guidance on how to surmount those challenges.

From the start, its work focused on the interrelationship between education, poverty, gender, ethnicity, language and disability, particularly in the world’s poorest countries. At its heart was the principle that if future generations are to enjoy successful, stable, safe and healthy lives, education is not just a “nice-to-have” – but essential. “The need for the REAL Centre is pressing,” former Australian Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, told the launch event. “It will make a difference in helping us to understand what works to make education more equitable. It will generate much light to educate every child, including every girl. The REAL Centre will be one of real achievement.”

On 12 June, 2025, researchers, policy actors, educators and practitioners will gather for REAL’s 10th anniversary conference. They do so at a time when anxieties about global education seem, if anything, more profound than they did in 2015. The retreat of Western governments from foreign aid is likely to compound the difficulties experienced by education systems in the Global South which are already feeling the effects of conflict, economic inequality, climate change alongside the aftershocks of COVID-19.

Yet despite these pressures, the prediction of achievement has held true. As the articles and reports summarised here demonstrate, over the last decade, the REAL Centre has shown how focused, collaborative research can advance equity and social justice in and through education. Academically, it has emerged as an international hub for such scholarship. Beyond academia, it has formed successful partnerships to shape policy and support lasting, positive change for communities in the Global South. As the 2030 deadline for the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals – including the commitment to achieving inclusive and equitable education for all – looms closer, REAL’s 10th anniversary invites us to reflect on these foundations, while also asking what comes next in a rapidly changing international context.

Raising the floor

A consistent call across the REAL Centre’s work has been to “raise the floor” on education. Amid a wealth of other insights for policymakers, its clearest message is that targeting disadvantaged students first will create systems that work for everyone.

The Centre was launched at a time when school access was expanding rapidly in much of the Global South. A new crisis was, however, already emerging. In 2014, the UNESCO Education for All Global Monitoring Report, of which REAL’s Director, Professor Pauline Rose, had been director before Cambridge, reported that 250 million children worldwide were unable to read, write or count, even though about half of them had spent at least four years in school.

Evidence from the REAL Centre has consistently shown that average attainment data which, in 2015, were still frequently used to shape education policy, conceal a more nuanced picture. Disaggregated analysis – using information such as household surveys and demographic data – is crucial when trying to improve education systems anywhere in the world. As Pauline Rose put it: “To make sure all children are both in school and learning, we should be asking which children are being left behind and why?”

This approach has informed REAL’s projects in collaboration with partners in countries such as India, Pakistan, Ethiopia, Ghana, Rwanda and Tanzania. Time and again, these studies have shown that the students most at risk of low attainment are marginalised groups: the very poorest, those in remote, rural areas, girls, and children with disabilities.

In 2017, a study by Ben Alcott and Pauline Rose, in collaboration with the PAL network, showed that even when controlling for other factors, household wealth and parental education drive learning gaps from the beginning of primary school. The study highlighted the need to address the disadvantage experienced by students from less wealthy backgrounds as early as possible – even before they start school – to prevent these effects from deepening.

A 2020 study by Dr Rob Gruijters, using PASEC data provided by an association of education ministries in Francophone Africa, similarly found that children from the poorest families consistently performed worse in basic literacy and numeracy tests because they were clustered in low-quality schools lacking even basic resources.

“If we really want to fix things,” Gruijters argued, “there needs to be a commitment not only to investing in education, but to ensuring that every school has a minimum level of support in staffing, training and resources.”

Teaching Effectively All Children (TEACh), a collaboration with CORD in India and IDEAS in Pakistan, provides one example of how the REAL Centre’s collaborative research has provided a strategic response to this challenge. The initiative, involving Professors Pauline Rose and Nidhi Singal, has provided robust evidence about which aspects of teaching most influence learning outcomes – particularly for children facing multiple disadvantages, including for children with disabilities. By assessing pupils both in and out of school, and tracking the relationship between learning progress and factors such as teacher characteristics and family background, the research offered detailed insights into the challenges teachers face in diverse classrooms, how they respond, and the kinds of support they need to teach all learners effectively.

As these and other studies have pointed out, poverty often intersects with other disadvantages. Addressing educational inequality, therefore, requires interventions that also tackle social norms, economic difficulties, infrastructure issues and other barriers.

REAL Centre research also shows that when education strategies do target marginalised students successfully, their more-advantaged peers also feel the benefits. A study co-authored by Professor Ricardo Sabates on work by the Campaign for Female Education (CAMFED) in Tanzania, for example, showed that for every $100 spent per girl, per year, the programme resulted in learning gains equivalent to two years of education for all girls and boys at those schools. Girls who received CAMFED bursaries were, meanwhile, 30% more likely to stay in education. “Helping the most marginalised children inevitably costs more and most cost-effectiveness measures only consider that expense against the impact on specific pupils,” Sabates said. “Programmes like CAMFED’s have spill-over benefits and are keeping girls in school who would otherwise have dropped out.”

Partnerships with organisations and institutions in the Global South are central to the REAL Centre’s approach to achieving lasting, evidence-based impact. A key example is Mapping Education Research in sub-Saharan Africa, a two-phase project launched in 2017 in collaboration with Education Sub-Saharan Africa (ESSA). The initiative has enhanced the visibility and accessibility of policy-relevant research on early childhood development and foundational learning produced by scholars in the region, through the creation of the searchable, regularly updated African Education Research Database. It has also helped build a network of African researchers, identified their needs, and connected them with relevant forms of support. In doing so, the project has not only helped close the visibility gap through which locally generated evidence is often marginalised, but has also challenged extractive research models by giving greater prominence the work of those closest to the context.

Read more

School segregation by wealth is creating unequal learning outcomes for children in the Global South (May 2020).

Spill-over effects show hidden value of prioritising education of poorest children and marginalised girls. (November, 2020).

Raise the Floor. (January 2022).

Championing girls’ education

At the launch of the REAL Centre in 2015, both the Vice-Chancellor, Professor Sir Leszek Borysiewicz, and former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard, highlighted the enormous numbers of girls who were excluded from education in the Global South – particularly those from poor households and those with disabilities.

This became an early focus for the Centre. In 2019, researchers produced a study for the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office examining girls’ education across a number of low- and lower-middle income countries which showed that for many marginalised girls, the global target of 12 years of quality universal education remained a “distant reality”. The report called for “high-level, visible political leadership”, which was echoed a year later with a call for a “global coalition of parliamentarians” to support gender equality in education. Both documents emphasised the need to address intersecting challenges, including gender-based violence, discrimination, and harmful social norms, that affect the educational opportunities of young women and girls.

From its inception, the REAL Centre has worked with international partners to improve girls’ education on the ground. A longstanding collaboration with the Campaign for Female Education (CAMFED) has produced valuable evidence about what works when trying to improve opportunities for marginalised girls, and why. In collaboration with the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, REAL Centre researchers have shown how CAMFED’s Learner Guides programme, through which young women mentor students in their communities, has not only improved learning but promoted a positive change in attitudes towards women and women’s education in contexts where their prospects have traditionally been limited.

Dr Rosemarie Mwaipopo, who led part of this research at the University of Dar es Salaam, has commented that the vast majority of those interviewed when assessing the Learner Guides initiative “attributed some change in gender norms to Learner Guides.” “It is clearly not down to Learner Guides alone,” she added, “but due to their unique mode of operation; reaching young males and females at the lower secondary school level within their school environs, sometimes sharing with them how to address gender-related challenges on a one-to-one basis, or consulting with grassroots leadership whenever the opportunity arises.” Similarly, Dr Nkanileka Mgonda, Co-Principal investigator and one of the report authors from the University of Dar es Salaam, said: “Arguably, the biggest driver of change is policy reform. What that means, though, is that Learner Guides can become agents of that change on the ground.”

This evidence base has, among other results, enabled CAMFED to raise further funding to support marginalised girls.

The REAL Centre has also undertaken extensive research to support UK government projects aimed at supporting the education of marginalised girls in the Global South. A 2021 report, commissioned by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, highlighted the urgency of challenges faced by marginalised adolescent women in many low- and middle-income countries who leave education early. It called for stronger protections against gender discrimination in the labour market, better social safety nets, and access to further training and formal education. This work helped shape the UK’s education priorities during its G7 presidency that same year.

In 2012, FCDO launched the Girls’ Education Challenge, with the aim of transforming the lives of more than 1 million of the world’s most marginalised girls through quality education and learning. The REAL Centre played a central role in the independent evaluation of these initiatives. A 2023 study led by Professor Nidhi Singal, for example, found that projects targeting girls with disabilities not only improved learning outcomes, but also transformed their aspirations and self-esteem, enabling them to pursue employment and greater independence. Singal has commented: “It is critical that we develop more focused interventions for these marginalised young women. Doing so could make a real, lasting difference not just within the classroom, but far beyond it.”

Another, collaborative assessment of the ‘Leave No Girl Behind’ initiative led by Professor Pauline Rose, and undertaken in partnership with the Oxford Partnership for Education Research and Analysis, Tetra Tech International Development and Fab Inc; focused on marginalised girls aged 10-19, similarly found that as well as enhancing basic literacy and numeracy skills, the initiatives had improved their life skills and well-being.

The evidence indicates that such programmes can generate ‘virtuous circles’. Girls who benefit from them, recent work led by REAL Centre researchers suggests, often become ‘agents of change’, who run life skills courses, support groups and mentoring schemes for others. They also become role models in their communities, creating ‘ripple effects’ that are crucial to challenging social norms and building sustained support for girls’ education.

At the same time, the Centre’s reports emphasise the need for sustained investment, structured alignment with national and local government priorities, and close collaboration with networks and organisations from the community level upwards. The GEC projects have worked, researchers argue, because they explored and understood the specific needs of marginalised girls and tailored their approach accordingly. Rose has reflected: “A single education aid project cannot reverse societal or economic constraints by itself, but it can lay the groundwork for a broader approach sustained by others, long after the original project comes to an end.”

Read more

A girl without education is nothing in the world (February, 2017)

Left behind adolescent women must be prioritised within sustainable development agenda. (February 2021).

Focused interventions for girls with disabilities fuelled ‘life-changing’ impact on aspirations and self-esteem. (May 2023).

Sustained, purposeful investment key to leaving no girl behind either in education or beyond. (October, 2023).

Mentors for under-privileged girls in Tanzania are challenging harmful gender social norms. (April, 2024).

Putting the early years first

In 2017, the House of Commons International Development Committee published the results of an inquiry calling for more UK spending on global education. Among other sources, this report used evidence from the REAL Centre which emphasised the need to prioritise early years education in order to meet UN Sustainable Development Goal 4: inclusive and quality education for all.

There is a broad consensus that pre-primary education is crucial for children’s cognitive and social development and, by extension, to breaking cycles of poverty. The Centre’s own research has repeatedly emphasised this point.

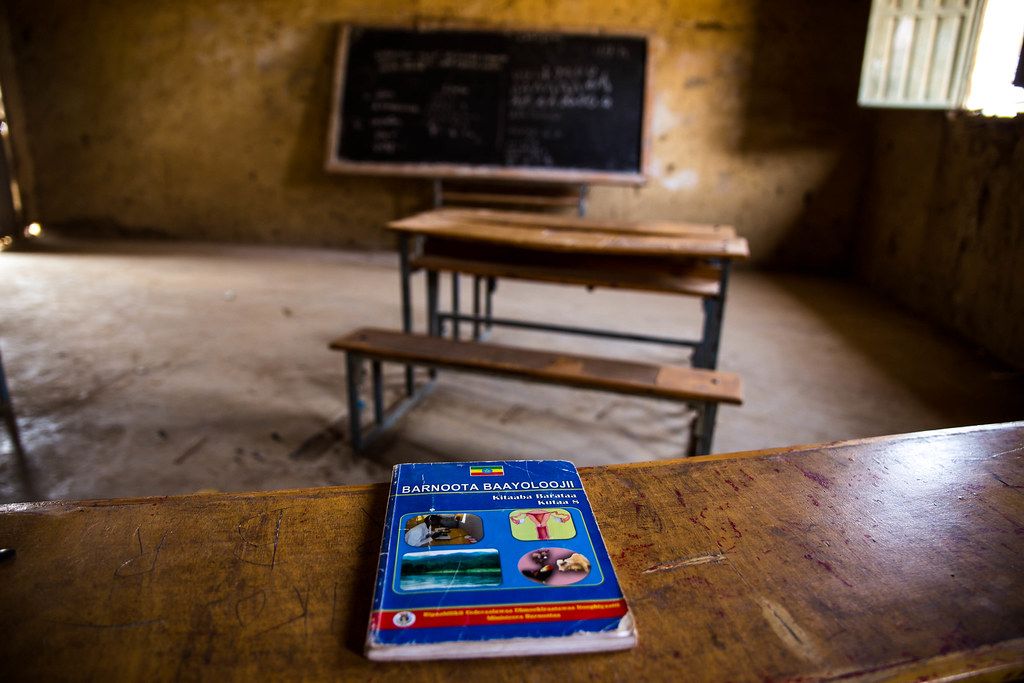

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic school closures, for example, a collaborative project with Addis Ababa University and the Ethiopian Policy Studies Institute showed that learning losses were far less severe among students who had undergone pre-primary education. However, the research also found that pre-primary education had been neglected in the country’s education response. “Pre-primary education raises particular challenges,” Professor Tassew Woldehanna of Addis Ababa University noted, “but that shouldn’t stop us from finding solutions. These issues need to be addressed now and not in the middle of the next emergency.”

At an international level, the REAL Centre has worked closely with the children’s charity, Theirworld, to monitor aid spending on pre-primary education.

Theirworld itself has recommended that 10% of education aid should be invested in this area. REAL Centre evidence was used in the case which led to this target becoming, first, a formal UNICEF recommendation, and, next, a target endorsed by 147 UN member states in the 2022 Tashkent Declaration.

Progress towards that target has, however, been limited. A 2023 analysis of early years aid spending post-pandemic, undertaken for Theirworld, showed that the share for pre-primary education had fallen after years of progress which had, itself, been glacial. This post-pandemic ‘dip’ was, perhaps, predictable, but the 2025 report suggests that the drop is continuing in what the authors describe as a new era of “cuts and conflict”.

Sarah Brown, the Theirworld Chair, has urged governments not to be short-sighted, arguing that: “investment in the youngest children is not just morally the right thing to do, but economically smart”. Even at a time when budgets are tight, the REAL Centre’s research has shown how this could be achieved. It highlights, for example, that in 2023, donors spent 24 times more on post-secondary education than on pre-primary. “We need to be much smarter about whom we fund and how,” Pauline Rose has said. “Instead of focusing on young people who make it to university, we should be targeting those children who never make it out of the starting blocks”. A pathway, in other words, exists – and the question now is whether those with the power to support pre-primary education will be sufficiently bold to take it.

Read more

Pre-primary education played protective role against COVID learning losses in sub-Saharan Africa. (February 2022).

Richest nations drift further from 10% aid goal for pre-primary education. (May 2023).

New era of aid cuts and conflict threatens educational lifeline of youngest learners. (May, 2025).

Monitoring the impacts of COVID-19 for marginalised learners

When the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, the REAL Centre rapidly pivoted to monitoring and advising on its effects on children across the Global South – especially the most marginalised learners. The REAL team was responsible for some of the earliest evidence of how school closures were affecting education in these parts of the world.

As further research was published, the full effects of school lockdowns became clearer. A collaboration with Addis Ababa University as part of the RISE Ethiopia project showed that the pandemic dramatically slowed academic progress, widening the already considerable attainment gaps between disadvantaged students and their peers. In countries such as Ethiopia, which was also facing conflict in Tigray at the same time, many of the poorest children, girls, those in remote areas and those with disabilities, received little or no education during the closures. The REAL Centre’s research also pointed to the challenges of reopening schools, however, given that many were under-resourced, crowded and lacked basic hygiene at a time when a vaccine was still months away. Further research, with colleagues from the Faculty’s Centre for Play in Education, Development and Learning (PEDAL) and Addis Ababa University, also found that the pandemic had “severely ruptured” children’s social and emotional development – not just their learning.

Collectively, this work illuminated the impact of COVID-19 on education in countries where these effects were far less visible, and far less well documented, than in the West. “There are multiple constraints affecting low- and middle-income countries which mean that the very poorest and most marginalised children are at even greater risk of dropping out of the system altogether than they already were,” Pauline Rose warned.

The message from these studies is therefore clear: recovery will depend on strategically targeted investment in catch-up learning for the worst affected students, the similarly targeted supply of essential resources, and a renewed focus on social, as well as academic skills.

The Centre’s work has done much to help shape recovery strategies in different contexts. For example, a study published in February 2022 for the UK government as part of the wider analysis of the Girls’ Education Challenge showed how community-based educators – especially women – had played a pivotal role in reaching at-risk girls during the crisis. Among other recommendations, this has highlighted the importance of integrating education with other key services and the need to support teacher wellbeing given the high levels of burnout experienced by those on the front line.

Another consistent message is that recovery is always possible, if strategies begin with those at most risk of being left behind. One hopeful signal came from a 2022 study in Rwanda in collaboration with Laterite, which found that a widely predicted spike in school drop-outs had not materialised as expected following lockdown.

There remains a risk that COVID-19 may nevertheless have stimulated a longer-term and more gradual rise in school drop-out rates in the Global South, especially among the most marginalised groups. “Keeping track of these children is really important,” Mico Rudasingwa from Laterite said. “By the time they reach adolescence, those from the poorest backgrounds in particular are in danger of dropping our early to support with income generating activities for the household.”

Read more

In Ethiopia, schools still lack basic means to contain COVID-19 as pupils return. (December, 2020).

School closures may have wiped out a year of academic progress for pupils in the Global South. (March 2021).

Teachers leading global drive to improve girls’ education became frontline workers during COVID-19 closures. (February 2022).

Students in Rwanda confound pandemic predictions and head back to school. (October 2022).

Stalled social skills, ruptured learning. (November, 2022).

Providing rapid reports on the educational impacts of conflict

The 2020s have witnessed a rise in humanitarian emergencies in conflict zones such as Gaza and Sudan, at the same time that international aid budgets are being cut. In these situations, education aid is often neglected in favour of other categories. Evidence produced by the REAL Centre has demonstrated that it should be given higher priority as it is vital to stabilising societies that have entered a spiral of decline.

In recent months, the Centre has produced rapid, data-driven research quantifying the effects of conflict on learning. A collaboration with the Centre for Lebanese Studies and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (UNRWA) in September 2024, for example, produced the first comprehensive assessment of the educational impacts of the conflict in Gaza.

This report found that, even according to the most optimistic prognoses, students in Gaza face years of lost learning. This is due to compounding effects of almost all schools being destroyed by Israeli airstrikes, the killing and regular displacement, of civilians, and the trauma faced by students and teachers. Similarly troubling was the finding that children’s faith in values such as human rights is also being eroded. The report argued that education in conflict zones should be considered not just valuable, but lifesaving, and called for urgent action to resume education, including the provision of psychosocial support, safe learning spaces, and targeted support for students and educators with disabilities.

Teachers themselves were shown to be under immense strain. “There is evidence of extraordinary commitment from teachers striving to maintain learning, but inevitably the deprivation, killings and hardship are affecting their ability to do so,” Professor Yusuf Sayed reflected at the time of the report’s launch.

Once again, this research highlights the importance of prioritising marginalised students in conflict situations, including refugee children and students with disabilities. These learners are frequently those whose learning is abandoned most easily during emergencies, and are then at risk of being excluded when systems begin to rebuild. The research has also highlighted the need for closer collaboration between government agencies, NGOs, universities and third sector bodies to address the underlying problems that inhibit educational recovery, such as financial instability, a lack of online learning infrastructure, and insufficient digital teaching capacity.

“Education is the only asset the Palestinian people have not been dispossessed of,” Philippe Lazzarini, UNRWA Commissioner General, said at the time of the report’s publication. “They have proudly invested in the education of their children in the hope for a better future. Today, hundreds of thousands of deeply traumatised school-aged children are living in the rubble in Gaza. Bringing them back to learning should be our collective priority.”

Read more

Palestinian education ‘under attack’, leading a generation close to losing hope, study warns. (September, 2024).

Driving evidence in policy, aid and systemic reform

Across its first decade, the REAL Centre has worked closely with governments, NGOs, donors and educators to translate research into action. From shaping major UK aid programmes to informing global strategy on disability and early years education, the Centre has influenced policy at multiple levels.

In 2018, REAL evidence helped to inform the UK Government’s Get Children Learning report, which committed £20.5 million to early childhood education. REAL’s work also informed the Leave No Girl Behind strand of the Girls’ Education Challenge, which led to an investment of £500 million to reach 1.9 million marginalised girls. The Centre’s work with the PAL network, meanwhile, influenced the incorporation of early learning targets into the UN sustainable development goals. As Dr Sara Ruto, the former Director of the PAL Network, later stated: “REAL Centre research has contributed significantly to discussions with UNESCO, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, UN Statistical Commission and others, advocating for the need for an early learning indicator to be included in the Sustainable Development Goals.”

REAL has also shaped policy and practice at both national and local levels. In Ghana, a study led by Professor Kwame Akyeampong in collaboration with Professors Rose and Sabates on the Complementary Basic Education Programme, which provides catch-up learning for out-of-school-children, helped secure 1% of the national education budget for its continuation. In Tanzania, REAL Centre evidence has helped CAMFED raise millions to expand support for marginalised girls.

Between 2018 and 2023, the REAL Centre and the ASER Centre studied the effects of an intervention by the Pratham Education Foundation in India to examine whether stronger and more direct bonds of accountability between schools and communities might help improve foundational learning for children who fall furthest behind. The findings showed that when parents, teachers and communities work together, learning outcomes – especially for the most disadvantaged – improve, and attitudes towards education shift significantly.

This project has offered critical insights for scalable, community-driven education reform, in India and beyond. As the ASER/Real Centre team observe in one of the key papers co-authored by Professor Ricardo Sabates from this research: “This underscores the vital role of parent-teacher interactions and their shared responsibility in shaping children’s learning outcomes… Community participation, facilitated through a collaborative and participatory approach between parents and teachers, can significantly improve children’s foundational learning, particularly for those who have not yet achieved foundational skills.”

In Ethiopia, research with Addis Ababa University and the Ethiopian Policy Studies Institute has shown how the education system needs to adapt to accommodate the needs of growing numbers of first generation learners whose parents never went to school.

It has also brought aid strategy itself under scrutiny. A 2022 REAL/Addis Ababa analysis of results-based financing for education in Ethiopia – an approach backed by institutions like the World Bank – identified some key flaws. Without dismissing the model outright, the report warned that some packages are being implemented without adequate, contextualised planning or appropriate data-gathering. Among other criticisms the study found that officials implementing the results-based programme in question had little grasp of what it meant or involved. “We didn’t expect everyone to have a comprehensive knowledge of what it involved, but we did expect they would at least be aware of it,” Dr Belay Hagos, from Addis Ababa University, commented.

The REAL Centre has also urged a shift in how wealth gaps in education are addressed. A study published in April 2021 using Young Lives data showed that less wealthy students with similar levels of ability to their wealthier peers often fall behind during the course of primary and secondary education due to structural and disadvantage. Dr Sonia Ilie, who led the study, said: “Even among children who do well to begin with, poverty clearly becomes an obstacle to progression”. This, and other studies, have recommended prioritising primary, or pre-primary, education in order to address wealth gaps in education at a much later stage. REAL’s collaboration with Theirworld indeed proved pivotal to persuading UNICEF to commit 10% of its education budget to early childhood education.

At a broader level, the REAL Centre has helped to make the case for research in international development itself. The Impact Initiative was a significant joint undertaking between researchers in the Global North and South, national governments and aid donors, involving the REAL Centre and the Institute for Development Studies. The initiative sought to identify synergies across research projects in international development and find ways to maximise their collective impact. The initiative showed that impact takes many forms – not just direct policy change, but also smaller ‘micro-impacts’ and shifts in relationships, attitudes and practices. The project was also in building new connections between researchers and policy actors, who together found new ways to drive agendas forward, for example, in disability education. The initiative remains a model for how research, collaboration and strategic engagement can drive real-world change.

Amid shrinking aid budgets – not least the UK’s decision to cut aid to 0.3% of gross national income by 2027 – the REAL Centre has consistently made the case that investment in education remains vital. Director Pauline Rose has described foreign aid cuts as “an ethical and strategic error”. The REAL Centre’s evidence – including its work with government itself – continues to make a powerful case for the principle that to deliver progress in health, climate resilience and economic growth across the Global South, education aid is fundamental to future success.

Read more

Grassroots accountability. (October, 2024).

Surging numbers of first-generation learners at risk of being left behind in education systems worldwide. (May 2020)

Poorly conceived payment-on-results funding threatens to undermine education aid. (March 2022).

Poor children are being failed by the system on road to higher education in lower-income countries. (April 2021)

Government aid cuts put girls’ education at risk. (November 2020).

New era of aid cuts and conflict threatens educational lifeline of youngest learners. (May, 2025).

Images in this story (top to bottom):

Secondary school students in Bagamoyo, Tanzania. Credit: CAMFED/Eliza Powell

REAL Centre logo (REAL Centre, University of Cambridge)

CAMFED Learner Guide Elizabeth leads a ‘My Better World’ self-development session in Tanzania’s Kilolo district. (Kumi Media/CAMFED)

Image of early years children provided by Theirworld.

An empty classroom in Haro Huba school, in Oromia region, central Ethiopia. Credit: UNICEF Ethiopia

17 August, 2024 Khan Younis Elementary Co-ed School “A” ©️ 2024 UNRWA.

Image of students in India licensed for use by kind permission of the ASER Centre, India.