BA in Education: Staff profiles

Gordon Harold is Cambridge’s first ever Professor of the Psychology of Education and Mental Health, and Director of the Andrew and Virginia Rudd Research and Professional Practice Centre. He has described his research at a fundamental level as being about how to improve the life chances of children and young people, and ensuring that they function well and feel able to do well in life. In particular, he is interested in the different factors which shape mental health challenges such as anxiety and depression. These, in turn, can affect other outcomes, including progress at school.

In their research, Gordon’s team work with professionals, children, families, educators and policy actors to support interventions and prevention frameworks that help young people to thrive. As he explains here, the developing research landscape is also changing the shape of the BA in Education.

I have been teaching on the undergraduate course in Education since I arrived at the Faculty in 2020.

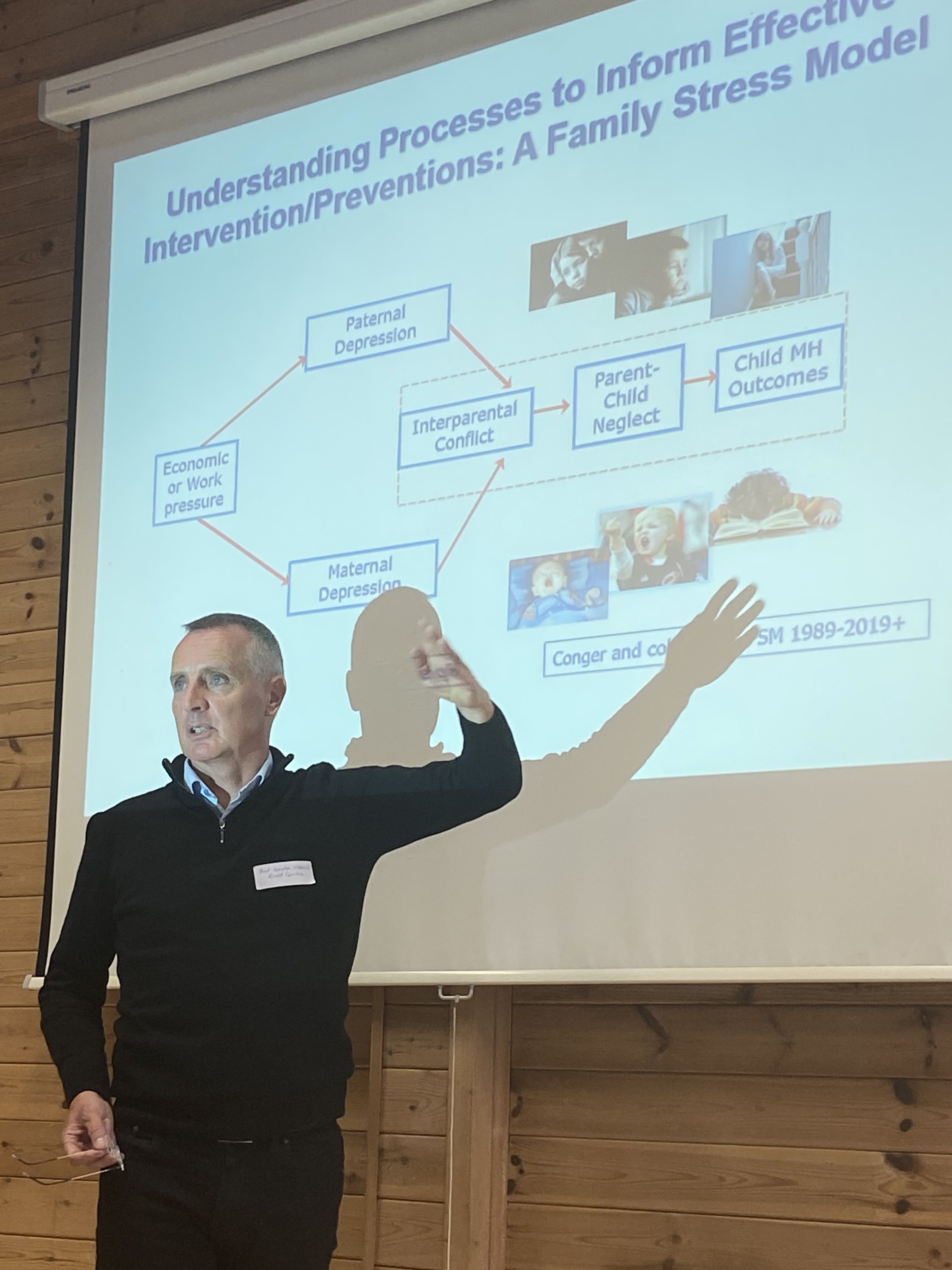

The Faculty shares several papers with the undergraduate course in Psychology and Behavioural Sciences. The topics we cover fall broadly under the heading of psychology, education and mental health. In my research, I am particularly interested in how we can support high-risk, vulnerable young people, as well as the families, carers and professionals around them. I examine the different factors that influence children’ and adolescents’ development and how early, effective interventions can reduce the risk of mental health disorders and promote better outcomes. Our perspectives on these challenges are changing, and this has gradually changed the way we teach students as well.

We get students thinking in ways that would normally only start at postgraduate level.

One of the most important qualities of the Education BA is that it offers an interdisciplinary framework for thinking about how we can help young people, bridging ideas and approaches that would conventionally have been kept apart at undergraduate level. For example, we get our education students to explore how behavioural scientists think about what constitutes ‘typical’ or ‘atypical’ childhood development, and how this might relate to different educational and related outcomes.

Cross-boundary thinking of that sort would normally happen at postgraduate level or when graduates embark on their professional training. We start earlier because it means that in a few years, when our students start to consider specialised careers in fields like teaching, educational psychology, social work or other aligned professional pursuits , they will already be aware of how those different disciplines connect and work alongside one another.

Having come into the University from another academic environment, I find this a particular strength of the degree. From the very start we are equipping students to draw together perspectives from a range of fields far wider than that offered by most undergraduate programmes. In that sense it is a very modern, forward-looking degree.

We need our future teachers, GPs, social workers and psychologists to be joined-up thinkers and practitioners.

We want our teaching to reflect transformations in how researchers and professionals are trying to help young people to do well in life.

A student starting the undergraduate degree today will be learning in a very different way to someone who started 10 or 20 years ago. In the past, the course might have focused more narrowly on how children learn, how they think, how we teach. That still matters – but today we also deal much more with subjects like the relationship between genetics and a child’s rearing environment, or the interplay between domestic conditions and mental health, and importantly how we help professional practice professions (such as teachers, psychologists, social workers and others) understand the interplay between these factors and their particular professional interests. Not so long ago those subjects were only seen as having an indirect bearing on education.

The reason we are now moving beyond that historically siloed curriculum strategy is because research consistently emphasises the need to think across the entire support system for young people if we want them to do well. If you are a professional working in that space, you need to be aware of the interrelationship between domestic adversity, social factors, biology and education. We need our future teachers, GPs, social workers and psychologists to be joined-up thinkers and practitioners.

We also need professionals who are critical thinkers

The course looks not just at how professional boundaries overlap, but how research, policy and practice intersect. What we are trying to do here is develop students’ ability not to take things at face value but to ask questions, and evaluate real-life challenges.

Sometimes students ask – quite reasonably – why I am teaching them about genetics on a course that’s meant to be about Education! But the answer is that it’s possible to identify cases of education policy in the UK – some of it very recent – which assumes that progress at school, or positive mental health, is tied to genetic advantages.

Research shows us that isn’t entirely correct: a child enters the classroom with certain genetic attributes, for sure, but there is a wealth of evidence that a warm, nurturing, positive environment can make a significant difference to someone’s educational attainment, social and emotional development, and future progress. So it is immensely important that students understand the scientific context so that they can engage with policy – at any level – critically and challenge it where necessary. Nobody expects everyone who works with young people to be a geneticist or indeed a formally trained psychologist. But we do need them to think and engage as interdisciplinary aware professionals, and to be capable of working with a full range of evidence to maximise the positive impacts that they can promote through their professional practice – this process starts with early professional pathway aligned education and training, such as that offered by our course.

This is critical to addressing rising levels of poor mental health. We urgently need educators and education professionals who are sensitive to the ways in which depression and anxiety, or other mental health challenges, affect the potential to learn. We need teachers who understand what it means for a student to be ‘at risk’ and the different strategies and agents which exist to address that.

I sometimes highlight that we are endeavouring to promote students who are ‘multilingual’ in their professional knowledge and discipline-based understanding, because they can think across psychology, education, genetics, methodology and other areas. But that is precisely the kind of thinker and future professional practitioner that we need to tackle the big ticket issues that society is facing: mental health difficulties, educational disengagement, inequalities, unemployment and reduced future life chances. Even if the future manifestations of those problems are sometimes unpredictable, this kind of agile, critical thinking will better position our students to take them on.

Working on the undergraduate course definitely keeps me on my toes.

Teaching on the BA in Education has also challenged me, in the best possible way.

Working on the undergraduate course requires me to make sure I am absolutely on top of the latest research and policy developments in different areas, so it definitely keeps me on my toes. By far the best part, however, is the engagement with the students. The students we have here are genuinely curious, thoughtful, and constantly ask for further information. Meeting their interests, stimulating those interests, and responding and engaging to the positive and inquisitive challenge they present in an informative and helpful way is the most rewarding part of the whole experience.

Find out more about Gordon’s research. Read more about the work of the Rudd Centre here.