Exhibition traces 200 years of Black representation in children’s literature

When Professor Karen Sands-O’Connor first met her future husband, she did what any children’s literature expert might and asked what he had read as a child. “He told me he didn’t read much,” she recalled. “His argument was, ‘I was never in those books, so why should I?’”

As the son of Jamaican immigrants, her husband was pointing out the absence of Black characters from books he had encountered in his youth. Sands-O’Connor suspected the reality was more complicated. Their conversation became the catalyst for years of research that has uncovered a history of Black representation in British children’s literature that is longer and more varied than many people realise.

Elements of the books, poems and illustrations Sands-O’Connor explored have now been brought together in Listen To This Story! – an exhibition that first appeared in Newcastle and has been brought to Cambridge by children’s literature researchers at the University of Cambridge.

It provides a distilled history of the authors, poets, illustrators and publishers who, across generations, worked to ensure that Black children could open a schoolbook or library book and see their lives reflected in its pages.

“Part of the idea was to show that even though the history is mixed, it’s not true that Black people were never in it – there are cases going back centuries where Black lives were celebrated,” Sands-O’Connor said. “At the same time representation is still far from ideal. When we first ran the exhibition, I saw children staring for ages at these images of other people who looked like them. It was really moving.”

As well as providing great joy, children’s literature can perpetuate inequalities or open opportunities

Sands-O’Connor has written extensively about Black and racially minoritised characters in children’s literature, including in Beyond the Secret Garden, co-authored with Darren Chetty. She developed Listen To This Story! with Kris McKie, then collections director of Seven Stories – the National Centre for Children’s Books – incorporating material from the University of Newcastle and the Black Cultural Archives. It ran in Newcastle in 2022 and has now been redesigned as a portable display for community spaces.

The visit to Cambridge has been arranged by the Centre for Research in Children’s Literature at the Faculty of Education. Joe Sutliff Sanders, Associate Professor said: “The lack of diversity in Anglophone children’s publishing is something we explore in our teaching, using Karen and Darren’s research. As well as providing great joy, children’s literature can perpetuate inequalities or open opportunities. This exhibit is part of our ongoing exploration of how art for children can keep improving.”

The history of Black representation in children’s literature is often presented either as one defined by racist and colonialist attitudes, or as a story of celebration and self-expression. The display suggests these two narratives constantly intertwined.

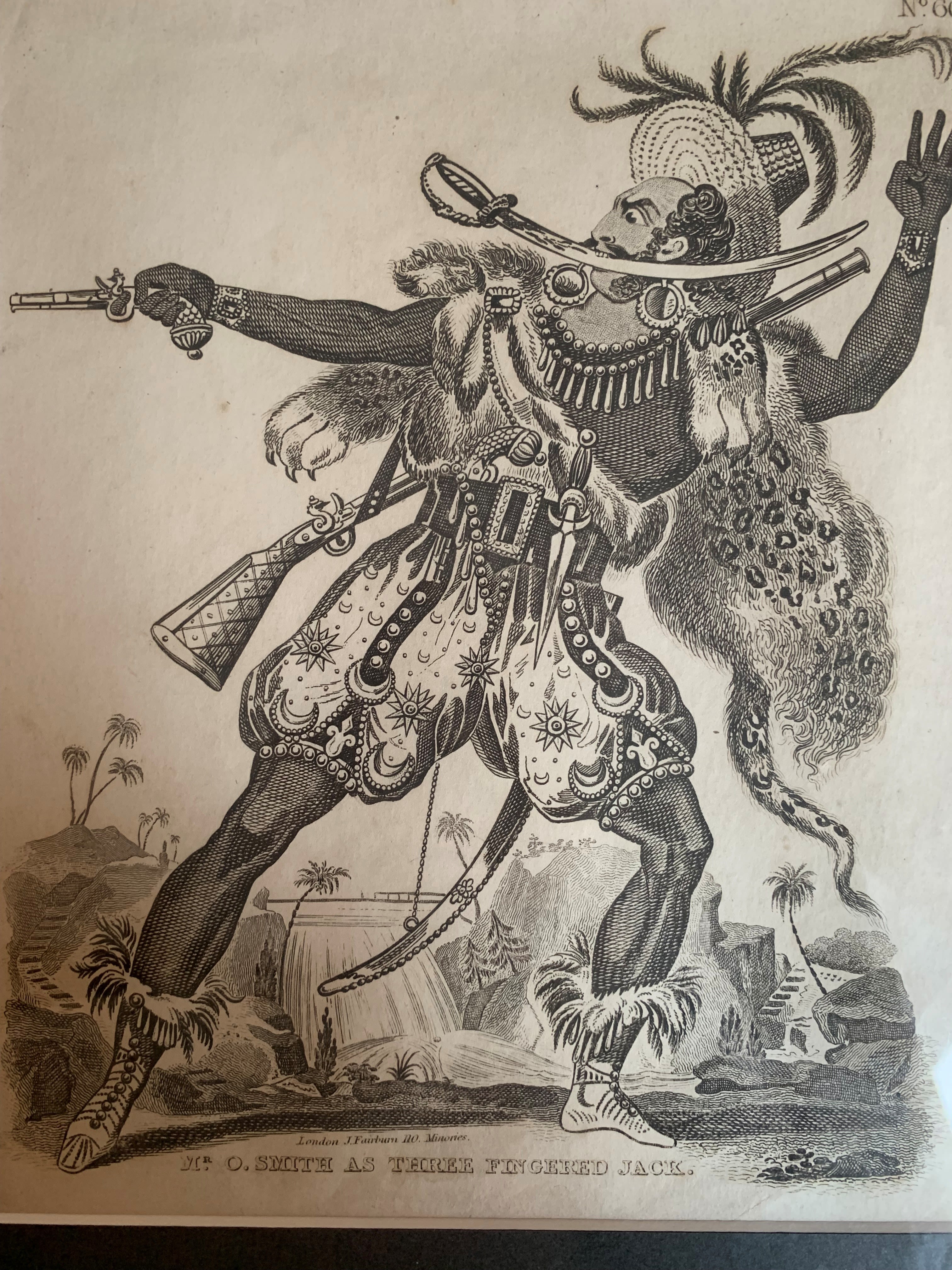

One early example is a poster for an 1808 pantomime about “Three-fingered Jack – the Terror of Jamaica”, based on the real leader of a community of runaway slaves. Jack was sometimes portrayed as a hero and sometimes – as in the pantomime – a villain. He is an example of a Black character appearing in early children’s culture who could be presented from very different, and sometimes prejudiced, viewpoints.

The exhibition also pictures Mary Seacole, a Jamaican nurse in the Crimean War, whose story was told for children in Noble Deeds of the World’s Heroines by Henry Charles Moore (1903). “There are problems with how Moore represented her and used the civilising rhetoric of Empire,” Sands-O’Connor said. “What interested me, though, was that she was shown doing important work and treated with respect. It wasn’t a negative account.”

The display then introduces early Black British writers and artists who helped to shape children’s publishing, including Una Marson: the poet, activist and BBC broadcaster. In London, Marson encountered persistent racism. She later returned to Jamaica and helped to run the Pioneer Press, which for the first time, offered young West Indian readers locally published children’s books about their own lives.

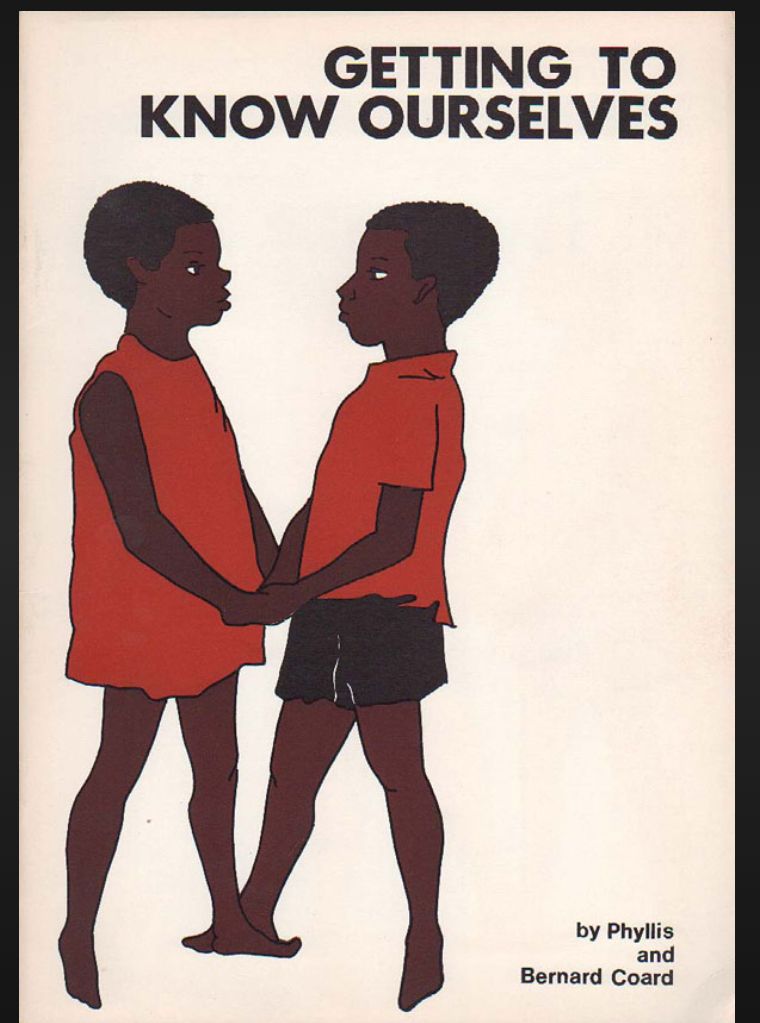

Black children’s publishing gained momentum as the children of the Windrush generation entered school. New independent publishers such as Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications and New Beacon Books began to provide a steady stream of literature reflecting Black experiences, but their limited reach into libraries and schools meant that many children did not encounter them.

Representation improved unevenly in the later decades of the century. The first picture book by a mainstream UK publisher aimed at the British market featuring Black children – My Brother Sean, written by Petronella Breinburg and illustrated by Errol Loyd – appeared in 1973. Well into the 1990s, many of the best-known children’s books with Black protagonists were still by white authors. “The argument was that there were no Black writers or illustrators,” Sands-O’Connor said. “There were – but they weren’t being picked up by mainstream publishers.”

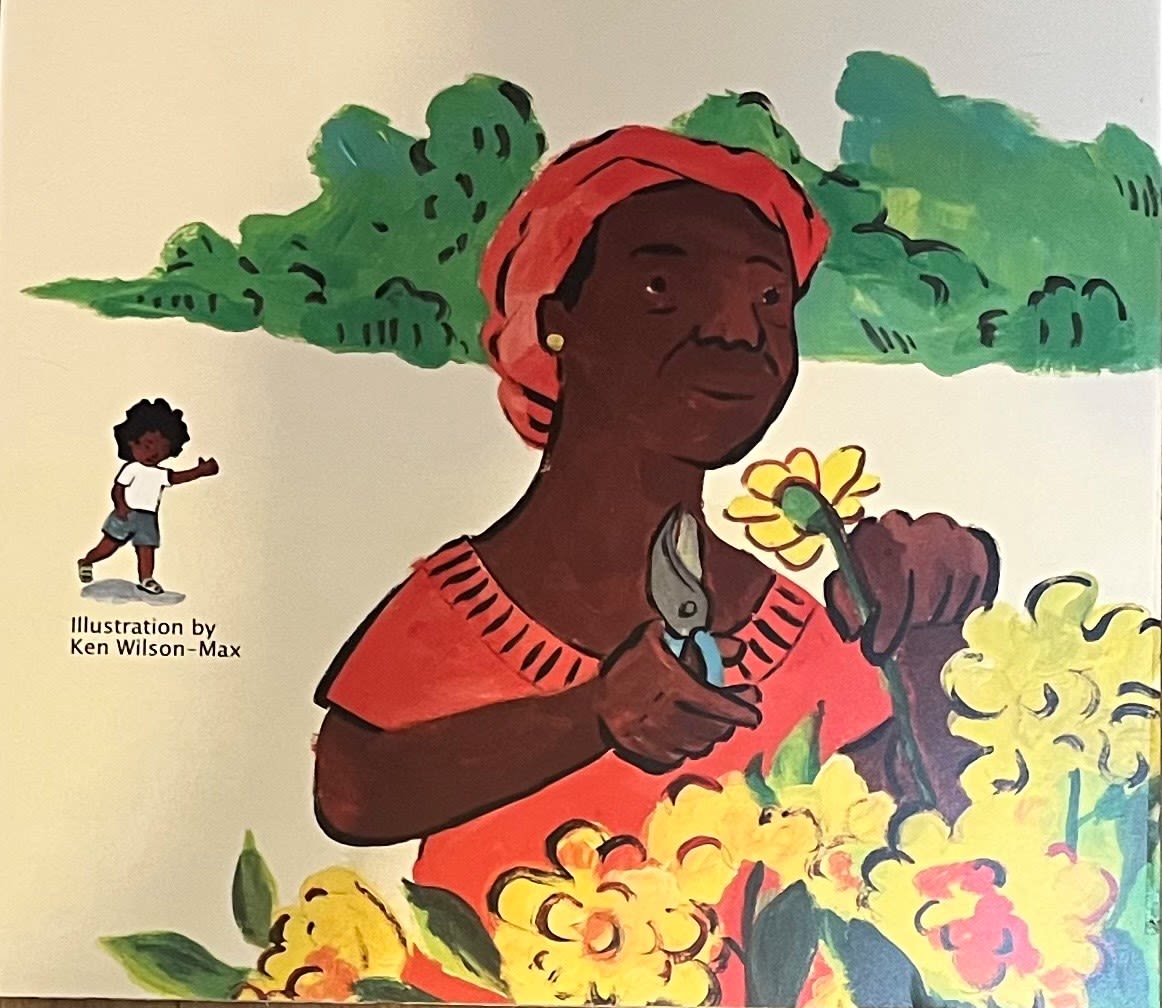

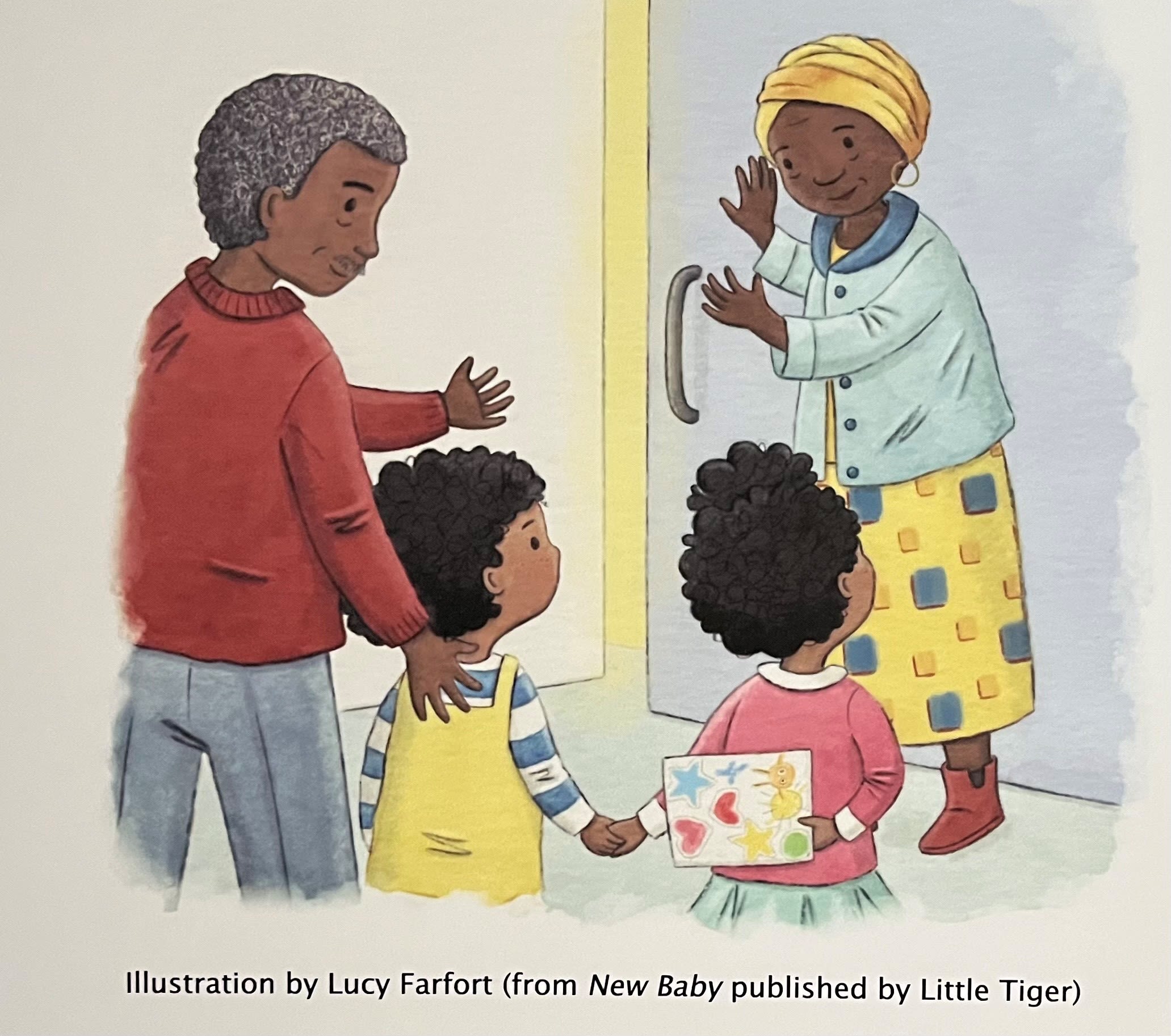

The exhibition suggests that these earlier efforts laid vital foundations for stronger representation today. It highlights the work of illustrators such as Lucy Farfort and Ken Wilson-Max, whose work often represents the range of heritage traditions and cultural experiences encompassed by Britain’s many different Black communities.

People should never be a trend in publishing

As a member of the steering committee for the Reflecting Realities study, which surveys ethnic representation in UK children’s publishing, Sands-O’Connor stressed that any progress remains fragile. Recent reports show that while 33% of Britain’s school-age population are from minority ethnic backgrounds, only about 24% of children’s books feature racially minoritised characters.

“The situation is better than it was, but most children’s books have a shelf life of about five years,” she said. “The progress we’ve made could easily be lost.”

Maintaining pressure on publishers is crucial. “People should never be a trend in publishing,” Sands-O’Connor added. “Ghost stories, science fiction – those are trends. Groups of people are not. They should always be represented.”

Cllr Alison Whelan, Chair of the Communities, Social Mobility and Inclusion Committee at Cambridgeshire County Council, said: “As a Council of Sanctuary, we are committed to creating a welcoming and inclusive environment for everyone. It’s vitally important that all Cambridgeshire’s children and young people see themselves represented when they come to library, so I am very pleased that Cambridge Central Library is hosting this important exhibition.”

Listen To This Story! runs at Cambridge Central Library from 15 December, 2025 to 16 January, 2026.

Images in this story (top to bottom):

Main publicity image for exhibition by illustrator Errol Lloyd / O. Smith as Three Fingered Jack. Theatre card from 1813, published for J. Fairburn.Illustration of characters from Eco Girl (Otter-Barry 2022) by Ken Wilson-Max. / Illustration by Lucy Farfort for New Baby (Caterpillar 2022) written by Isabel Otter. / Cover illustration by Ricardo Wilkins of Getting To Know Ourselves (Bogle L'Ouverture 1972) by Phyllis and Bernard Coard