Inaugural leadership forum for heritage language schools launched in Cambridge

Cambridge has become home to the first leadership forum for community-based ‘supplementary’ education, informal schools which provide extra education for children from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds.

The Cambridge Community School Leadership Forum, which met for the first time in November, is a collaborative space where community leaders, teachers and managers can share information and advice to support bilingual and migrant children.

Community-based heritage language schools are typically volunteer-run and often operate at weekends. They offer students from different cultures a safe and structured environment to learn about their background, usually by studying their ‘mother tongue’ languages and cultures.

Cambridge, which is one of England’s most linguistically diverse cities, has more than 30 such schools, including three Chinese and two Arabic schools, a Polish school, the oldest in Cambridge, a small 12-pupil Persian School, and schools for the city’s Bulgarian, Hungarian, and Spanish and Tamil communities – to name but a few.

A growing body of evidence suggests that supplementary schools can also support English language acquisition, social and emotional learning, and students’ successful social and cultural integration. At present, however, most function on the fringes of formal education, without direct funding or support.

Under the auspices of the Centre for the Study of Global Human Movement at the University of Cambridge, the new forum is a joint initiative by Cambridge Research in Community Language Education (CRiCLE) and the non-profit organisation, Cambridge Bilingual Groups, aiming to address this by enhancing collaboration between schools, families, communities and the University.

These schools often feel as though

they are adjacent to wider society.

Yongcan Liu, Professor of Applied Linguistics and Languages Education at the University of Cambridge, said: “These schools often feel as though they are adjacent to wider society. It is often extremely difficult for them to get funding, resources, or policy support independently. The first step towards getting the help they need – and in many ways the most important – is bringing people together.”

Cambridge has often been described as one of the best places in Britain to grow up multilingual. Data from the 2021 census shows that about 17% of people living in Cambridge use a language other than English at home. The number of heritage language schools has grown rapidly: from 24 to 33 since 2019. There is also increasing demand for further schools to support the city’s Bengali, Malayalam, Romanian and Urdu-speaking communities. These languages are among those most widely spoken by bilingual children in Cambridge and Cambridgeshire, yet do not have a community school.

Many scholars of heritage, language and migration believe these schools have considerable benefits for students. For example, studies have pointed to associations between multilingualism, stronger cognitive functions, and improvements in students’ academic performance.

There is also evidence that the schools play a significant role in social integration: helping migrant children to settle into their new communities, and providing many students with a vital support network which helps them to navigate experiences of racism, discrimination and prejudice.

Liu, Y., & Hoare, L. (2023). Complementary schools as heritage language communities of practice: Reaching beyond language maintenance. In H. Pinson, N. Bunar & D. Devine (Eds.) Research handbook on migration and education (pp. 203-220). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Liu, Y., & Hoare, L. (2023). Complementary schools as heritage language communities of practice: Reaching beyond language maintenance. In H. Pinson, N. Bunar & D. Devine (Eds.) Research handbook on migration and education (pp. 203-220). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Their status and relationship to the British education system is both ambiguous and insecure, however. At various times over the past 50 years, encouragement was given to schools to embrace bilingualism and various initiatives were put in place to support heritage language schools.

This support has found itself in constant conflict with a strain of political thought which sees responsibility for teaching and learning heritage languages as lying outside mainstream education. As a result, there has been no sustained policy support for heritage language learning. There are thousands of community schools across the country, but without funding, some smaller schools have been forced to close.

Even within that context, academic and policy research into the role of heritage language schools has consistently found that they help students to become better learners, support positive social emotional skills, and enable them to positively combine a sense of their own cultural heritage with British identity.

In 2014, Cambridge’s then vice-chancellor, Professor Sir Leszek Borysiewicz, suggested the term “heritage” languages itself warranted reconsideration. “One in six children in English primary schools do not have English as a first language,” he said. “These are real languages: living languages that give people a huge insight into culture and give the children who can speak them additional opportunities.”

If you invest a little in these schools, they will repay that many times over in the contribution

they make to wider educational goals.

Without structured support, all supplementary schools, and especially smaller ones, are in a precarious position. The smallest such school in Cambridge, for example, currently has 12 students and no secure funding stream either from the government or from overseas.

Dr Anke Friedrich, director of Cambridge Bilingual Groups, said: “There are more than 2,000 children attending heritage language schools in Cambridge, which is a substantial figure. The time and effort they spend acquiring literacy and higher level oral skills in their home language – and sometimes the frustrations they experience doing so – should be recognised more widely. Children are not sponges when it comes to language learning. It requires a lot of concerted effort from them, their families and their communities to achieve fluency of all types. Heritage language schools are one piece in the network that enables this.”

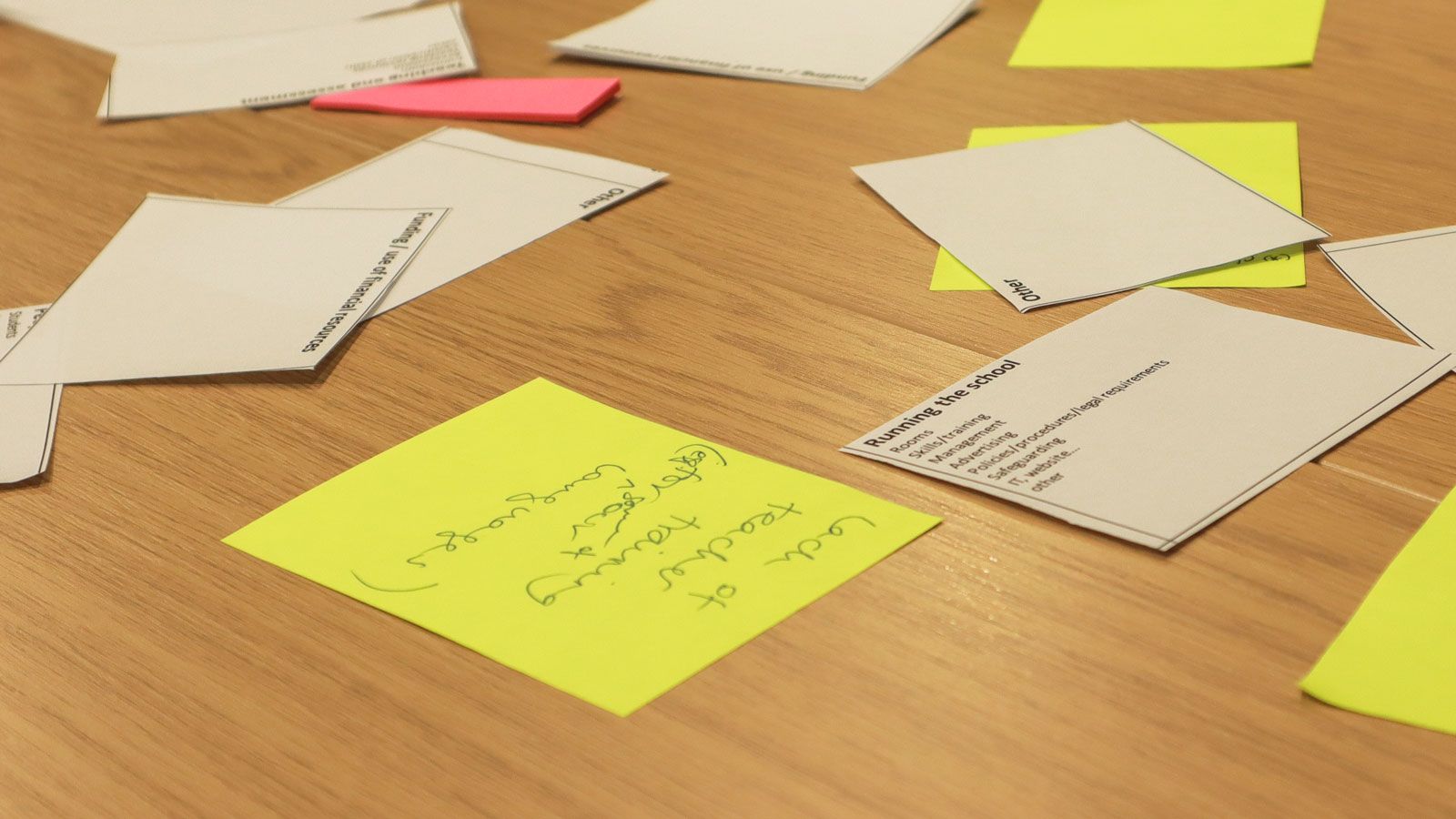

In response to these challenges, the new Forum is providing a platform for collaboration, information-sharing, help and advice. A total of 35 teachers and leaders attended the first meeting in November, to discuss issues that ranged from logistics and fundraising to more detailed pedagogical questions.

This extends the work of the Cambridge Research in Community Language Education Network, based at the University’s Faculty of Education, which seeks to combine the knowledge and skills of different partners to support bilingual children; especially those who find themselves ‘on the move’ and living in a new country.

Liu argues that there is a strong desire across Cambridge to help migrant children and build a civic identity that embraces different cultures. Many of the city’s biggest companies and employers, for example, offer practical support like diversity funds. He adds, though, that supplementary schools will not be able to make use of these resources unless they are first given a space where they can find out about them, share information, and cultivate awareness and trust.

He believes that the University can be the “missing link” which allows that connection to form. “Lots of research shows that if you invest a little in these schools, they will repay that many times over in the contribution they make to wider educational goals.” Liu said. “I think many politicians and policymakers have not quite realised how powerful and cost-effective they can be. Our hope is that this forum will help everyone with an interest in supplementary heritage language education to think differently, and find new opportunities.”

Cambridge Research in Community Language Education Network is a research initiative hosted in Cambridge’s Faculty of Education which aims to provide a platform for practitioners, policy makers, researchers, and students to engage in critical debates on language, heritage and migration. Cambridge Bilingual Groups provides a regional support network for all bilingual groups in and around Cambridge.

Thanks to Dr. Jim Anderson, co-director of the Multilingual Digital Storytelling Project, Goldsmiths, University of London, for his contribution to this article.

Images in this story (other than where credited) taken at the inaugural meeting of the Leadership Forum. Credit: Yue Zhou