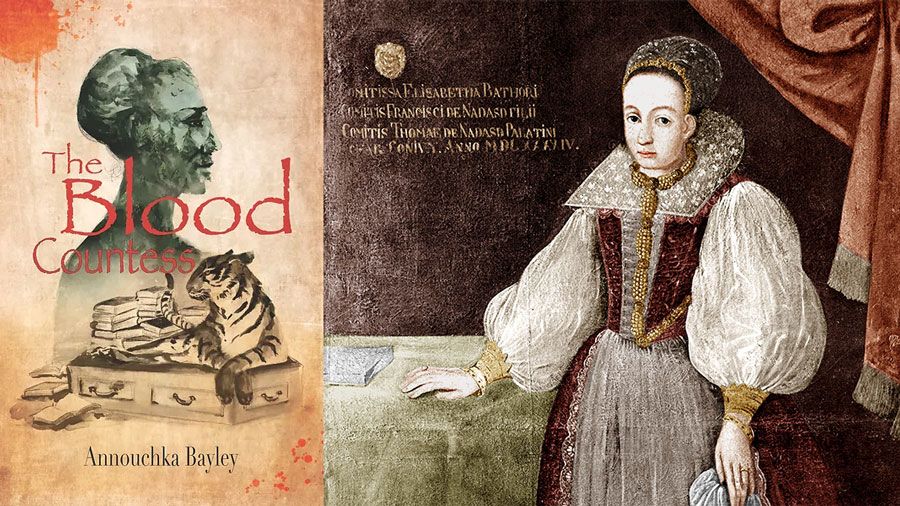

New exploration of “Countess Dracula” reveals a 17th-century radical whose crimes were faked

A new novel which enters the world of the 17th-century countess renowned as history’s “most prolific female murderer” suggests she was actually a revolutionary and book smuggler whose killings were a fiction.

Elizabeth Báthory was a powerful Hungarian noble who allegedly murdered hundreds of young women in her castle at Csejte, in modern-day Slovakia. The most extreme stories about her hold that she slaughtered up to 650 victims, believing that bathing in their blood would keep her young.

While these gruesome accusations are disputed by historians, the facts of Báthory’s case, which are sparse, have rarely been allowed to get in the way of the story. Báthory appears as a vampiric monster in literature, film and even heavy metal. The Guinness Book of Records lists her as history’s most prolific female murderer.

The new book, The Blood Countess, by University of Cambridge academic Dr Annouchka Bayley, is based on months of research using surviving, original sources in translation. Like some revisionist historians, she concludes that the accusations were entirely false. She also goes a step further, however, arguing that the countess was a religious subversive, book smuggler and radical feminist. Combined with her status as a wealthy widow, this made her a prime target for a 17th-century witch hunt.

Perhaps surprisingly, Bayley chose to rewrite Báthory’s story not as history, but historical fiction. Her novel intertwines Báthory with the semi-autobiographical tale of a female academic whose identity becomes entangled with the countess during a near-death experience.

The approach draws on Bayley’s wider scholarship at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, where she studies “diffraction”.

This is a term borrowed from quantum physics, and refers to using different thinking and learning strategies to ‘enter’ concepts and study them from the inside. Her book can be read as a straightforward novel, or as a “diffractive” encounter with Báthory.

Its additional ‘Easter egg’ physics references meanwhile moved one academic reviewer to describe it as: “Quantum physics made very sexy”.

“I first encountered Báthory when I was 17 and working in a bookshop,” Bayley said. “Countess Dracula by Tony Thorne, which is about Báthory’s case, had just been published. The whole story just seemed a massive stitch-up. I promised myself that one day I would rewrite it.”

The Imperial establishment didn’t just try to displace her; they went to great efforts to create a monstrous vision that completely erased her identity

Báthory was born in 1560 into a powerful noble family; her relatives included the governors of Transylvania, a semi-independent territory at the fringes of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1575, she was married to Ferenc Nadasdy, a general who spent much of his time away with Imperial armies fighting the Ottoman Turks.

Nadasdy died in 1604, and Báthory inherited his castle at Csejte. There, she supposedly committed her horrific crimes under the pretence of running an academy for young women. In 1610, Gyorgy Thurzo, the Palatine of Hungary, launched an investigation which assembled 300 witness testimonies to accuse Báthory of torture and murder. She died, while under house arrest, in 1614.

Báthory was never formally tried and her case is riddled with holes. Most damningly, just one body was found, although testimonies mentioned coffins frequently leaving the castle. As a widow and a Protestant during a regional, pro-Catholic Counter-Reformation, Báthory was a natural target for other nobles who coveted her wealth. In addition, the Emperor, Matthias, owed her money at the time of her imprisonment.

Bayley believes the accusations against her were more than a toxic mix of patriarchy and political circumstance, however. Her research revealed that Báthory’s academy – which is usually depicted as a courtly finishing school – was actually a place where young women learned to read and encountered some of the new ideas flowing out of Reformation Europe. It is also evidenced that Bathory had a printing press in her husband’s castle, Sarvar, and on her first site visit to Csejte, Bayley also found tunnels leading out of the castle which prompted her to incorporate this into her fictional imagining of what really might have been going on.

Báthory may also have had access to the highly controversial writings of the Spanish scholar, Michael Servetus. During the Counter-Reformation, efforts were made to destroy all copies of Servetus’ Christianismi Restitutio, a proto-Unitarian text. During Báthory’s lifetime, copies reappeared – in none other than Transylvania, a major Protestant outpost.

More than just a wealthy woman in the wrong place at the wrong time, Bayley believes that Báthory was teaching and distributing radical religious ideas. “Perhaps those coffins weren’t carrying bodies, but smuggling books out of the basement,” she said. “It seems significant that the Imperial establishment didn’t just try to displace her; they went to great efforts to create a monstrous vision that completely erased her identity.”

The Blood Countess merges Báthory’s story with its other heroine, the modern-day academic, Vera. “Both characters come up against similar challenges, particularly relating to how histories are used to write our world,” Bayley said. “They end up being able to sort of ‘hear’ one another across time.” As Vera writes Báthory’s story, she is transformed by it. Bayley hopes readers will similarly emerge from their encounter with Báthory thinking differently about how, as we shape knowledge, knowledge also shapes us, which is why she chose to write this as fiction. “After all, we’ll never truly know what exactly went on, but that doesn’t mean we can’t learn from it! Storytelling does that – and this idea is a major component of the novel.”

These deeper themes reflect her research interests in entanglement, diffraction, and their potential role in education. Academically, Bayley explores how rather than simply “downloading” information from teachers and books, knowledge and ideas can be experienced and ‘lived’, particularly through the arts. “Fictioning” knowledge, as in The Blood Countess, is one such approach.

“When we challenge the nature of knowledge, we also start to see how the world could be made differently,” Bayley said. “That’s something Báthory lived and did, and it’s also a question for education, particularly given that our current education system clearly isn’t functioning as well as it used to and needs reform. The Blood Countess takes those ideas and runs with them through multiple layers. In some ways, it’s everything I teach at Cambridge, represented in a novel.”

Images in this story: Cover of The Blood Countess by Annouchka Bayley and Anonymous portrait of Elizabeth Báthory, Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons