Self-sustaining learning: What happened when Huntingdon sixth formers took a mini-PGCE?

An experimental project at a Cambridgeshire schools trust in which sixth formers stepped into the shoes of teachers has found that the approach can generate valuable forms of learning that complement more conventional lessons.

The “Student Outreach Society” – or SOS – is an after-school initiative developed within the ACES Academies Trust, Huntingdon. Over several months, 17- and 18-year-olds from Hinchingbrooke School devised and prepared activities for younger children inspired by their A-Level subjects.

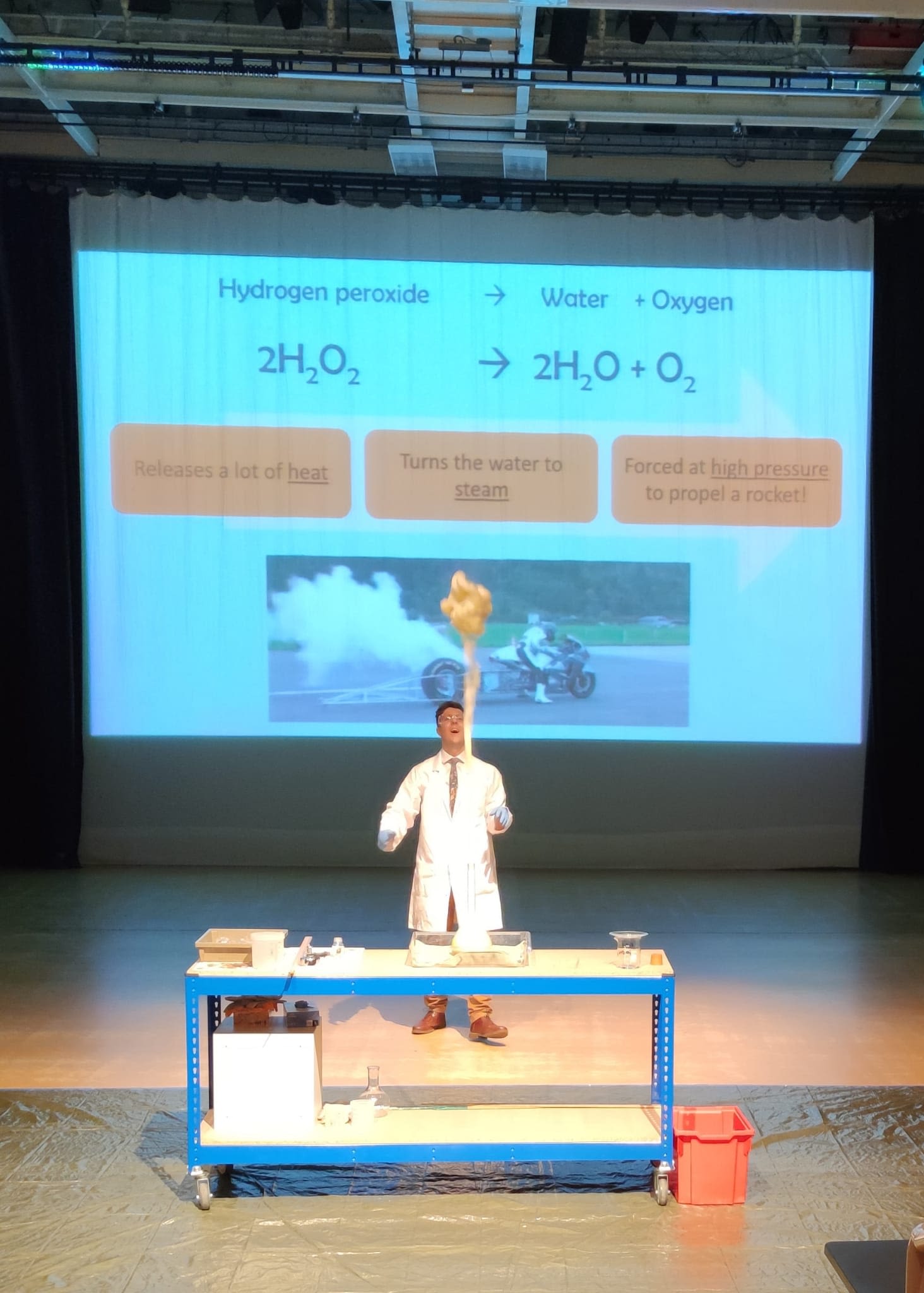

Taking on teaching roles, they then ran learning activities for Year 5 pupils at Cromwell Academy aimed at inspiring the next generation. During an after-school “festival of learning”, they introduced younger children to topics including optical physics, the workings of the human brain, and the battlefield tactics of Alexander the Great.

The initiative has been described as a “mini-PGCE for sixth formers” by its initiator, Charlie Pettit: a science teacher and learning lead for the ACES Trust who also educates future teachers on the (official) Secondary PGCE programme at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge.

What emerged, he said, was a rare form of “self-sustaining learning”.

“The amazing thing was that the professional teachers in the room just stood back and witnessed learning happen by itself,” Pettit said. “Young people spoke to other young people, shared ideas, treated each other with respect and worked together. Watching that unfold so positively was very emotional.”

You spend time investing in these individuals so eventually they don’t need you. That was happening in real time.

SOS stemmed from Pettit’s interest in the science of learning and motivation – in particular Self-Determination Theory (SDT). This argues that learning is enhanced when education meets three psychological needs: Autonomy (control over behaviour and choices); Competence (feeling capable and effective); and Relatedness (feeling connected and purposeful).

He has long sought to find ways to make learning – especially in science – more engaging in this way. “Some of the most powerful learning experiences happen when, instead of just being fed information, students can ask questions, share ideas and influence their own learning,” he said.

Pettit’s first attempt at stimulating a “self-sustaining” dynamic was in 2022, when he ran a Christmas lecture-style evening of science for ACES primary students and their parents that encouraged children to “think like scientists”. Despite its popularity, he felt it did not go far enough. “I hope it inspired the children, but what happens next?” he said. “Maybe that spark burns out because it has nowhere to go.”

Charlie's Christmas lecture-style science event in 2022

Charlie's Christmas lecture-style science event in 2022

You can view education as something set down in a scheme of work and tested in exams, but intuitively we know it is also something more.

In response, he found himself drawing inspiration from his other day job on the Cambridge PGCE. Given that this aims to cultivate teachers who think critically and flexibly about their subjects, Pettit wondered if getting students to teach others might strengthen their engagement with learning?

Initially, he established a “Science Outreach Society” at Hinchingbrooke, which prepared sixth form science students to run a lesson on dissection for children at Cromwell Academy in 2024. This, Pettit felt, got closer to his goal – but he also felt he still had too much control over the lesson planning. As the professional science teacher in the room, he, rather than the students, had designed and guided the initiative.

The answer, he realised, was to step back and open the project up to students in any subject. This changed his role, from showing them how to teach science, to showing them how to teach.

In October 2024, Hinchingbrooke therefore began weekly SOS sessions: effectively a crash-course in teaching for A-Level students. Those who signed up were studying a range of subjects such as history, chemistry, and psychology. Drawing on elements of Cambridge’s Initial Teacher Education programme, they explored topics such as how to communicate with younger pupils, include everyone in a lesson, manage behaviour, and facilitate learning.

Working in 10 teaching teams of two or three, the sixth formers designed an activity that had to engage primary pupils through questions and thinking tasks and ensure that “learning happened”. How they did this and what they taught was up to them but informed by their work with Pettit.

On the afternoon of the event, stations were set up around a primary assembly hall, each led by one of the teams. Pettit gave the countdown, then stood back with his colleagues while the primary students circulated.

He described feeling “redundant in the best possible way”. “It’s what being a teacher is,” he said. “You spend time investing in these individuals so eventually they don’t need you. That was happening in real time.”

Hannah Connor-James, headteacher at Cromwell Academy, agrees. “The sixth formers showed real leadership and an understanding of what it means to break down ideas, communicate and support younger learners,” she said. “Seeing older students not only share knowledge, but model how to teach it, was powerful. Learning can be shared, developed and ignited on both sides when young people inspire younger people.”

Pettit characterised the outcome as a form of “flourishing”. The primary pupils explored new ideas in a structure that constantly interrogated their thoughts. The sixth formers deepened their understanding while developing leadership and communication skills and managing younger children. Students who were usually quiet, he noticed, stepped forward and led confidently.

“You can look at education as something set down in a scheme of work and tested in exams, but intuitively we know that it is also something more,” Pettit said. “SOS seems to capture that richer, multi-faceted aspect of school. I think our sixth formers came away with a deeper sense of what learning can be.”

In the longer term, he hopes to analyse how and why SOS worked and develop a resource that could support other teachers interested in similar approaches.

He emphasises that this is not a prescription for teaching. “I wouldn’t dispute the criticism that it won’t work everywhere or that there are other ways to motivate students,” he said. “None of the approaches available for teachers are necessarily wrong. But, as teachers, we do need to keep thinking about the different ways that young people learn. There is never a silver bullet that solves that challenge for everyone.”

Images in this story provided by Charlie Pettit