New wellbeing model for heritage language learning could help multilingual students flourish

New research shows that a better understanding of how children from immigrant families and minority backgrounds experience wellbeing through learning their heritage language can help them to overcome the vulnerability and anxiety they often encounter. The research calls for “a positive turn in heritage language education”.

In a large-scale project involving hundreds of Chinese heritage students, researchers at the University of Cambridge showed that heritage language education, beyond academic benefits, can potentially play a crucial role in students’ socio-emotional wellbeing and integration.

An estimated 20% of children in the UK come from homes where a language other than English is spoken, often learning these languages at volunteer-run ‘complementary’ heritage language schools at weekends.

While most heritage language learning therefore typically happens outside formal education, the Cambridge project strongly suggests it can be pivotal to supporting the wellbeing of students who often feel like the “odd ones out” at school. The researchers, Dr Yue Zhou and Professor Yongcan Liu, from the University’s Faculty of Education, developed an assessment tool, the Language Learner Wellbeing Scale (LLWS), which measures bilingual children’s wellbeing in diverse heritage language learning contexts.

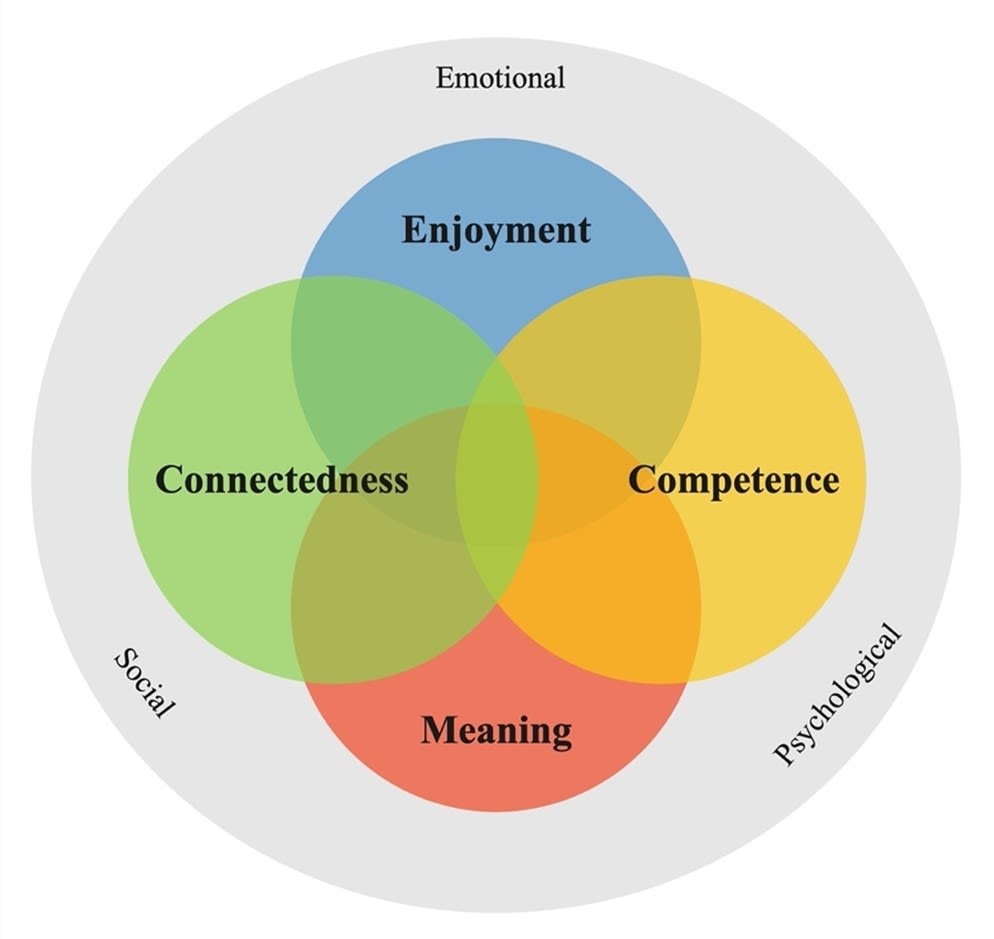

Their latest study tested the LLWS with more than 500 young Chinese language learners. It revealed four distinct aspects, or ‘factors’, of wellbeing that heritage language learning can potentially promote: ‘enjoyment’, ‘connectedness’ (with family, friends and community), ‘meaning’ (a sense of the language’s personal significance to the learner) and ‘competence’ from mastering new skills.

Heritage languages are often spoken by children who experience distinctive wellbeing issues.

Writing in the International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, the authors argue that there is a strong case for a ‘positive turn’ in heritage language education that puts wellbeing at its heart.

Zhou, who led the study as part of her doctoral research at Cambridge and is now at the University of Nottingham, said: “Heritage language learning should be about more than linguistic ability. It has the potential to support the happiness, pride and social engagement of children for whom these languages are very closely tied to questions of wider identity.”

“Heritage languages are often spoken by children who experience distinctive wellbeing issues,” Liu said. “Learning them can help to address the feelings of self-doubt and vulnerability that they frequently experience as they try to balance their own cultural background with their relationship to wider society.”

The project is the first to provide an evidence base for a theoretical wellbeing model specifically for heritage language learning, offering a pathway for bilingual children to thrive in education and more widely. It focused on student ‘flourishing’ – a combination ‘hedonic’ wellbeing (feeling good) and ‘eudaimonic’ wellbeing (feeling competent, motivated and functioning well).

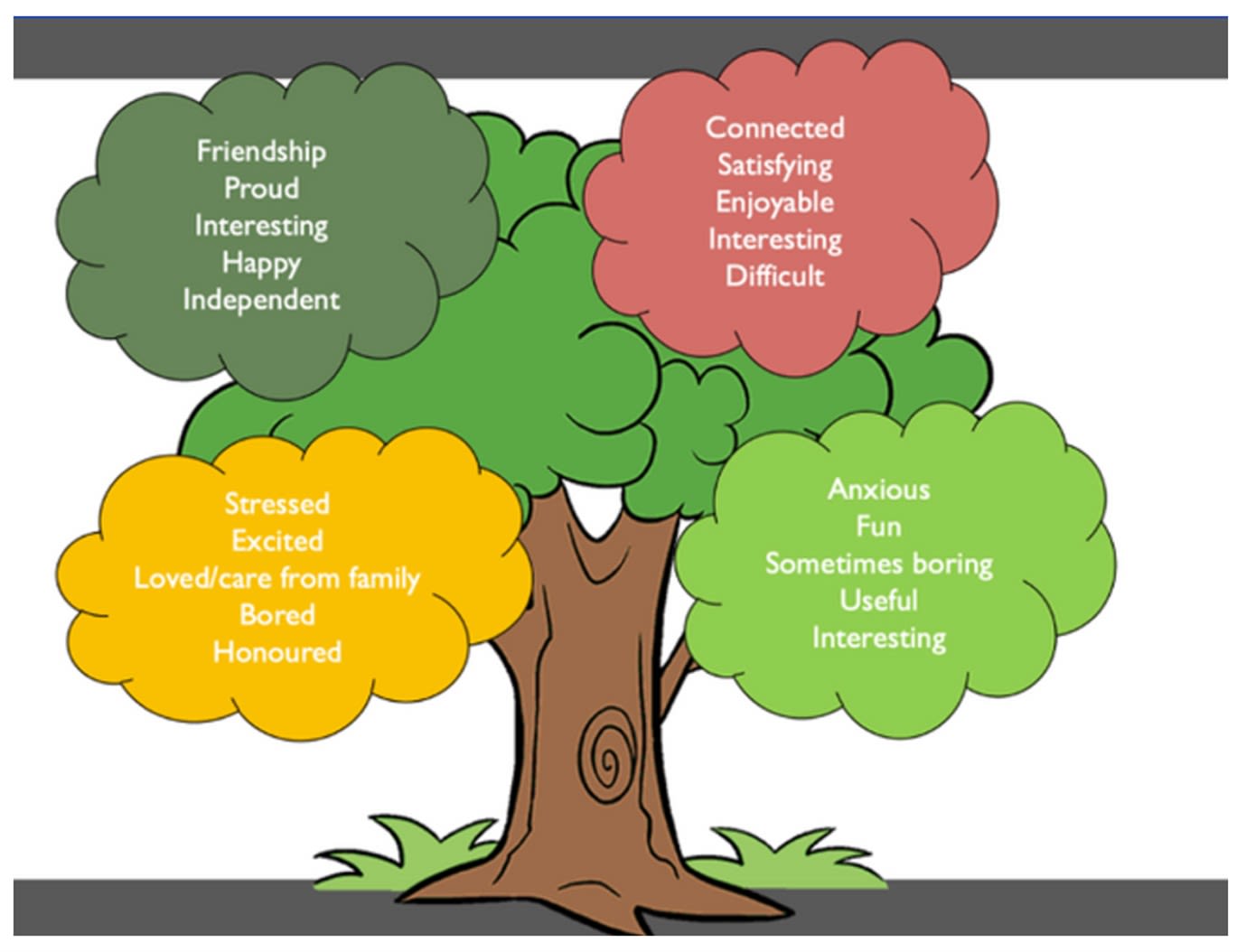

In an initial phase, Zhou and Liu ran focus groups with 40 young British Chinese language learners. Using techniques like drawing, collage-making and open-ended discussions, they explored how learning their heritage language might support flourishing. The students described various types of wellbeing, including particularly enjoyable educational activities, their pride in being able to use Chinese, and the connection learning it gave them to family and friends. They also highlighted that Chinese language schools provided them with an important sense of belonging because, as 15-year-old Qiuyu explained: “you don’t really feel like the odd one out.”

Building on these initial insights, which were published in October, the researchers developed the LLWS questionnaire; with input from linguists, educational psychologists, and Chinese heritage language teachers. After piloting the tool, they tested it with 545 Chinese language learners from different complementary schools.

The LLWS asked students to rate how often 24 statements applied to them, on a scale of ‘never’ to ‘always’. The statements included: “I feel competent and capable using Chinese”, “I feel that people recognise my ability in Chinese”, and “I enjoy learning Chinese so much that I lose track of time”.

The completed questionnaires were then used in rigorous statistical testing to confirm that the approach represented a reliable and consistent measurement tool. The findings provided a clearer picture showing bilingual children’s wellbeing can be actively promoted through four dimensions.

Four dimensions of wellbeing through heritage language learning

Enjoyment

The positive feelings students gain from language learning activities that are challenging, new and engaging. Student feedback from the focus groups suggested that this may, for example, include learning games, role-plays and group work.

Connectedness

The sense of belonging learners acquire from studying a heritage language. This social dimension of wellbeing is often overlooked but is crucial for minority students who often experience acculturation challenges. For instance, Qianqian, aged 12, described how learning Chinese strengthened her relationship with relatives in China: “Sometimes we Facetime them, and sometimes when they come over here I can speak Chinese with them, and I think that's an aspect of my wellbeing,” she said.

Meaning

The sense of purpose and self-worth students gain from feeling emotionally connected to their cultural roots. For many, learning a heritage language reinforces their identity and uniqueness. As 11-year-old Ziqing expressed, “I feel special knowing another language…like knowing something only I know in the school.”

Competence

The confidence and pride students gain from their developing linguistic abilities and is closely linked to how they overcome learning challenges.

The authors stress that these four factors overlap and need to be combined in effective educational interventions. Potentially, however, both this model of understanding, and the accompanying LLWS tool, provide a basis for teacher professional development, as well as tailored resources and pedagogical strategies to support wellbeing through heritage language learning.

Further research is needed to understand whether the framework can be applied to language learning in general, but Zhou stressed the model’s versatility. “At the very least this four-factor model should provide educators with a basis for exploring how wellbeing can be developed through language learning in general,” she said. “I hope it will be particularly useful to complementary schools and help them to reflect and build on their practice.”

References

Zhou, Y., & Liu, Y. (2024). A “positive” turn in heritage language education: Multilingual children's voices on language learner well-being. System, 125, 103446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103446

Zhou, Y., & Liu, Y. (2024). Language learner well-being in heritage language learning: conceptualisation, measurement, and a pathway to flourishing. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2024.2419428

Image: Jerry Wang, Unsplash.