Grassroots accountability

What happens when schools become directly accountable to their communities?

Schools are often seen as being responsible to the children and families that they serve, but in many places their primary accountability is really to the government authorities which set and monitor educational standards. This concept is known as the “long route” of accountability. It assumes that, by meeting government guidelines, schools are also meeting the wider population’s needs. In reality, however, the needs of their immediate communities could be very different.

At the same time, many parts of the world have experienced an expansion of education with most children now enrolled in school. This educational expansion has brought new challenges for teachers and educators, such as more ethnolinguistic and cultural diversity in classrooms, requiring innovative pedagogical approaches to support learning. Unfortunately, the learning needs of many children have yet to be met; often they are enrolled in school for several years but leave without even basic literacy and numeracy skills. This has been characterised, by some international organisations, as a ‘learning crisis’.

Given the potential of communities to be involved in supporting their children’s education and the role of teachers and educators to support learning in schools, could these two things be linked? If schools were able to build stronger and more direct bonds of expectation and accountability with their communities, would foundational learning improve, especially for those children who fall furthest behind?

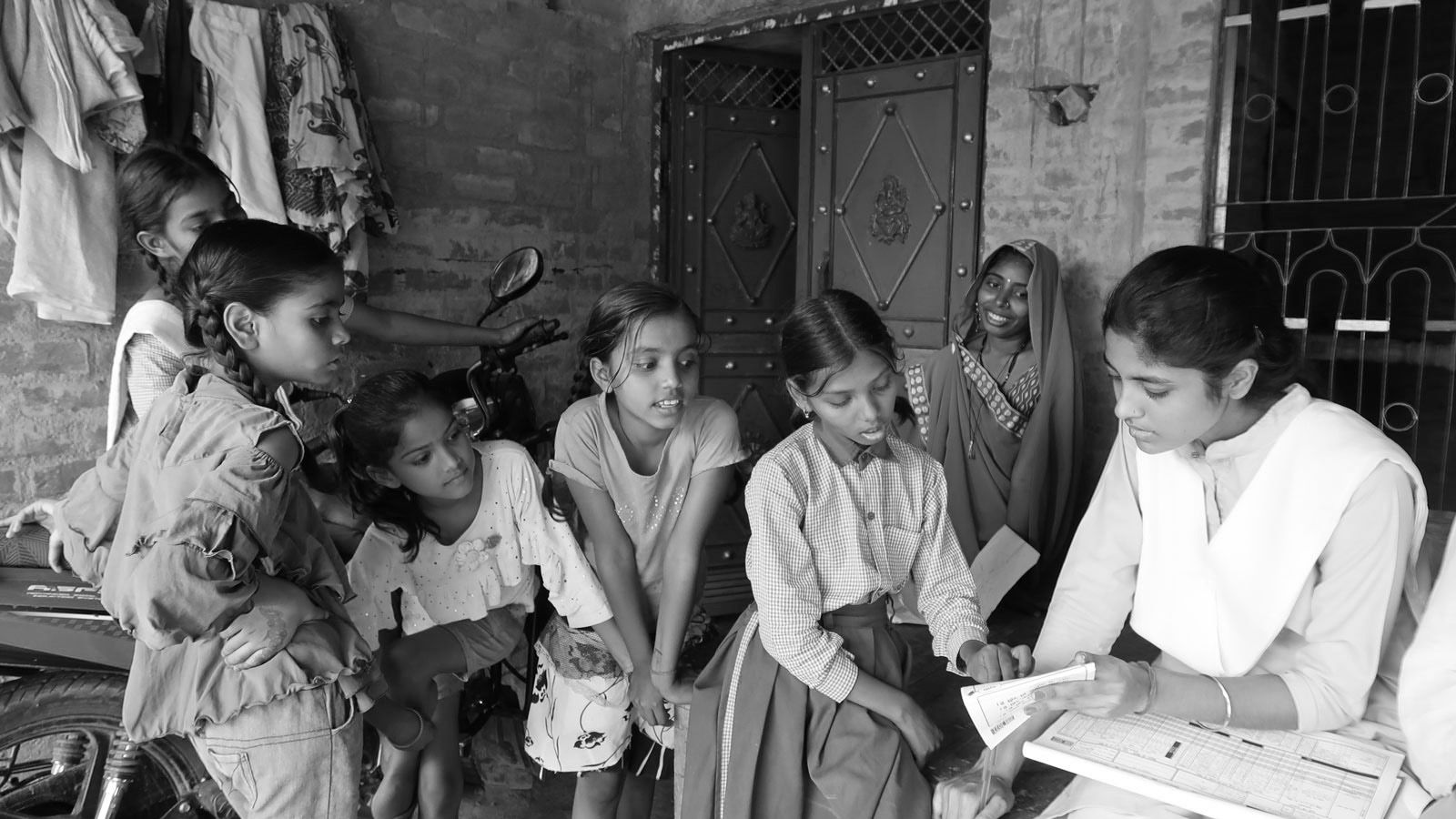

From 2018 to 2023, the University of Cambridge’s Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre and the ASER Centre in India studied the effects of the Pratham Education Foundation’s school-community level intervention in Sitapur district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, involving approximately 24,000 children from 850 government schools in 400 villages. The findings of this study suggest that when education is seen as a collaborative endeavour that involves everyone and takes a community-first approach, the benefits can be considerable. Foundational learning, especially for the poorest and least advantaged students, improves. The attitudes and perceptions of teachers and parents also undergo a significant shift.

This summary outlines the goals and structure of the project, Accountability from the grassroots in India, as well as some key findings; offering insights into how community-driven accountability could enhance education quality – particularly for those who need it most.

Partners

REAL Centre, Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge

ASER Centre, India

Pratham Education Foundation, India

Funders

Funding for this project was from the UK Economic and Social Research Council (Grant number: ES/P005349/1) and from the Mars Wrigley Company Foundation.

Introducing Accountability from the Grassroots in India.

Learning in India: Key Facts

Learning among school children in India has remained well below curricular expectations over the past two decades.

Annual Status of Education (ASER) reports indicate that in 2022, across rural India, only 42.8% of all students in grade 5 could read a grade 2 level text and 25.6% could solve a three- by one-digit division problem.

Results from the ASER surveys have consistently shown that the gap between abilities and curriculum expectations starts early and widens over time.

A 2015 Cambridge study showed that learning levels are linked to wealth: students from the wealthiest 20% of families are more than twice as likely to develop basic literacy and numeracy skills by the end of primary school, compared with the poorest families.

Many children currently in school are first generation learners. About one third have a mother who never went to school (ASER 2022).

Previous research suggests that teachers often blame parents for their children’s poor learning. A UNESCO report also indicates a blame game from other stakeholders, between parents, teachers, unions, NGOs, civil society organisations, and governments.

The intervention

Accountability from the grassroots was built on previous Pratham interventions promoting community engagement with children’s learning.

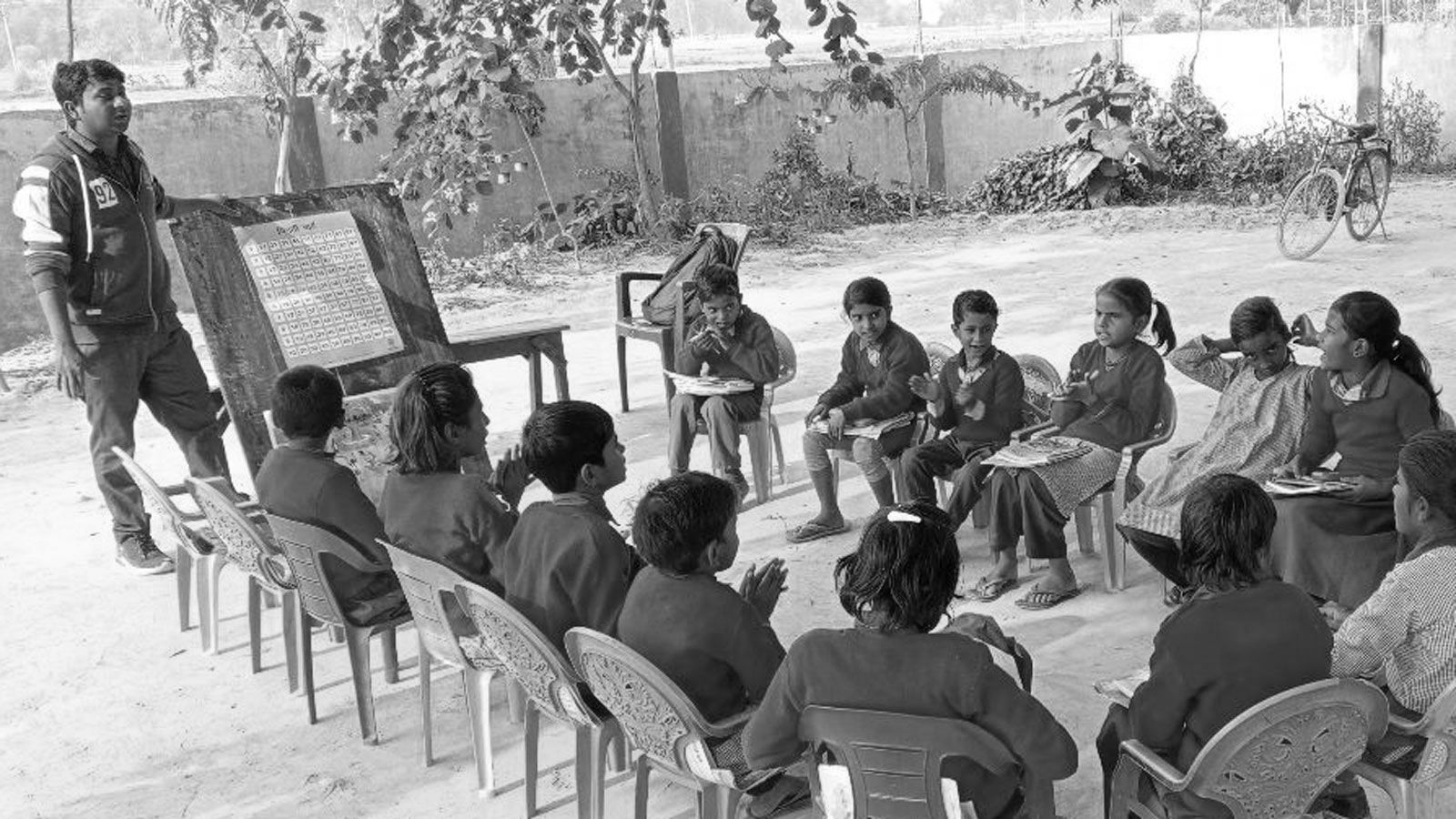

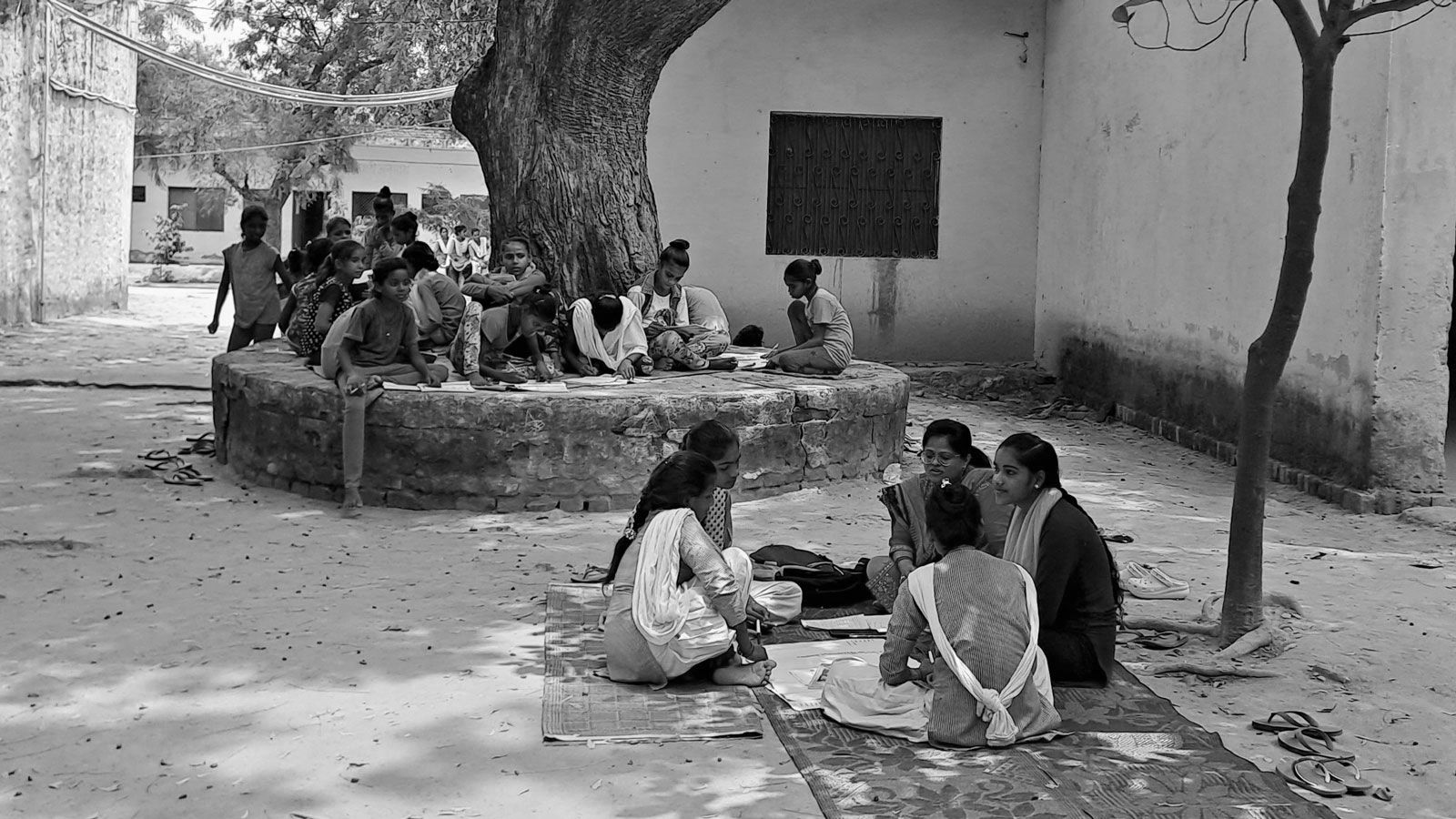

An intervention called PAHAL (‘Take Initiative’) comprised community-level activities such as developing village report cards to provide information about children’s learning levels within that community; volunteer-led classes for students outside regular school hours, and creating reading and study groups for students themselves, in which parents and siblings were encouraged to get involved.

A second intervention, PAHAL+, targeted school teachers and added new collaborative activities to improve school-community engagement. These included opportunities for parent-teacher meetings, support for parents to get involved with their children’s homework, and mechanisms enabling teachers to participate in the wider range of community-level activities established through the original PAHAL programme.

By comparing the effects of both PAHAL and PAHAL+ with the impacts of no intervention at all (using a control group), the study explored whether and how improvements in school-community relationships improved these stakeholders’ accountability for children’s foundational learning.

The approach

The study was designed as a Randomised Control Trial (RCT) with two treatment arms and a control group. It took place in rural communities in Sitapur district of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. The research deliberately targeted children in grades 2, 3 and 4 who could not read at grade 2 level. These were the low-achieving students who, it was hoped, the intervention might help most.

The study sample came from 400 villages in Sitapur which had at least two government schools. These villages were randomly assigned to the PAHAL+ intervention (200 villages), PAHAL (100 villages), and a control group which received no intervention (100 villages). An assessment of reading and arithmetic to students in grades 2-4 was conducted in the 850 government schools located in these villages, and approximately 24,000 students with poor reading ability were randomly selected into the sample.

As well as tracking children’s foundational learning over time, the research used surveys to study the perceptions, attitudes, and actions of both teachers and parents. This was supported with data from classroom observations. The research also involved in-depth case studies of three specific village communities where the intervention appeared to be taking root, and one where it was not; as well as 17 in-depth interviews (five head teachers, six regular teachers and six para teachers), and two parent-teacher meeting observations.

Initial findings

Unsurprisingly, given that students with low reading levels were selected by design, the participants’ foundational skills were very poor. Across all sampled Grade 2-4 students, barely a quarter could read more than individual letters. Similar patterns emerged for numeracy.

The initial findings also provided evidence of weak relationships between communities and schools. Although over half of the surveyed teachers reported conducting monthly parental meetings, only a third of the parents surveyed had visited the school during the academic year when the study took place while 71% could not name a single teacher at their child’s school. Teachers and parents generally expected each other to be more involved in educating children. 92% of parents initially said it was a waste of time to meet with teachers; 43% of teachers said parents were not doing enough to support children’s learning.

Disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic

Unfortunately, COVID-19 disruptions – as well as a variety of other unforeseeable events (such as prolonged school holidays due to extreme weather) – meant that only the short term effects of the PAHAL and PAHAL+ interventions could be measured in the end.

Despite this, the research provided some compelling evidence of how community-focused interventions can change the picture described by the initial findings. Some of the key findings of the project are explored below.

Find out more

Introduction to the project by Professor Ricardo Sabates, Faculty of Education.

REAL Centre Research and Policy paper: Children’s foundational reading and arithmetic in Sitapur District, Uttar Pradesh.

Nanda, M. (2022). Collaboration or Compliance: A multiple case study approach exploring teachers’ perspectives on interactions with parents within the framework of social accountability in rural Sitapur, India [Apollo - University of Cambridge Repository]. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.102174

1

Foundational learning improves when parents, teachers and communities work together.

Findings from the Randomised Controlled Trial at the heart of the project showed that both the PAHAL (community-focused) and PAHAL+ (community+school focused) interventions improved foundational literacy and numeracy skills, especially for those children who exhibited the lowest levels of attainment.

The PAHAL+ intervention showed that children’s foundational skills improve most when their parents are more engaged with their school and education. Encouraging schools to be more accountable to communities by strengthening the ties between parents and teachers could have significant benefits, especially for children who are furthest behind. For these children, education works best when the adults closest to them share responsibility for supporting their learning.

The study compared schools in 400 villages in the Sitapur district of Uttar Pradesh. In this study, 100 villages received the PAHAL community-based education intervention; 200 received the PAHAL+ intervention which encouraged collaborations between the community and schools, and 100 received no intervention. The students who were monitored were low-achieving, mostly from low socio-economic status groups and, in many cases, first generation learners. The researchers carried out baseline literacy and numeracy tests pre-intervention and follow-up tests about a year later.

Both PAHAL and PAHAL+ interventions significantly improved the children’s literacy and numeracy skills by around 8 to 10 percent as compared to the control group. Both interventions were found to be effective at improving foundational skills, particularly for those at the lower end of the skill spectrum. Moreover, there was a significant improvement in the advanced level literacy and numeracy skills, as well, such as reading a paragraph and performing subtraction problems, particularly in the PAHAL+ intervention.

PAHAL+ increased the likelihood of parents being invited to visit their child’s school by 7.3 percentage points compared with the PAHAL programme. Unfortunately, there was no evidence that parents actually became more inclined to take teachers up on this offer!

However, parents in the PAHAL+ programme who did visit the school were more likely to have interactions with teachers about their child’s learning, which may explain the corresponding upswing in academic performance among those children.

School attendance by PAHAL+ students was also 6.7 percentage points higher compared with the PAHAL group, and PAHAL+ students were more likely to study independently or with peers outside school. One additional effect of this was that these families relied less on costly and less equitable forms of educational support, such as private tuition.

Find out more

Kumar, D., Sunder, N., Sabates, R., & Wadhwa, W. (2024). Improving children’s foundational learning through community-school participation: Experimental evidence from rural India. Labour Economics, 102615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2024.102615

UKFIET blog: Involving the community in raising children’s foundational learning outcomes: evidence from India.

Oriel Square blog: Engaging schools and communities to support children’s learning.

2

Educators need to be supported to build on children’s current ability levels.

The project collected data from about 1,800 primary school teachers about their perceptions of low achieving students’ reading capabilities.

Around 40% of these teachers inaccurately assumed that low-performing students had reached the expected level of foundational literacy, when in truth they could often not even read simple words.

This highlights an urgent need to equip teachers, through pre- and in-service training, to assess students more accurately, identify those who need extra help, and tailor their pedagogical approach accordingly.

Teachers’ perceptions of their students’ academic skills and their ability to assess students accurately are clearly essential so that they can teach at an appropriate level. However, existing evidence suggests that their perceptions are often inconsistent with reality, especially in the Global South, and in particular with regard to low-performing students.

Students included in the Accountability from the Grassroots sample were, by definition, unable to read at Grade 2 level. The initial learning assessment showed that most were reading well below this level: 9.4% could read a simple grade 1 level paragraph, 9.5% could read individual words but not more, 47.6% could only recognise individual letters and 34% were at the “beginner” level (meaning that they were unable even to identify letters).

As part of the study, the teachers of 16,360 of these students were shown a grade 2 level text similar to the one used for the students’ reading assessment, and asked whether they thought individual students could read at that level. Comparing teachers’ judgement with students’ actual reading ability showed that on average, teachers responded accurately in the case of about 55% of these students, meaning that they overestimated the reading ability of close to half of these students.

The scale of teachers’ perception gap was often considerable. Of the 7,330 students whom teachers thought could read a grade 2 level story, more than 70% were only at beginner level, or only able to identify individual letters. Teachers were more likely to overestimate the reading ability of students in higher grades than lower ones.

In general, this pattern did not vary by teacher or school type, suggesting the problem is system-wide. Notably, teachers’ qualifications or years of experience did not significantly affect the accuracy of their judgement. However, women teachers and “para-teachers” (teachers typically locally recruited to temporary teaching positions), as well as those with a lower work burden, were more likely to have an accurate sense of low performing students’ attainment.

In addition, across all 400 participating schools, head teachers completed a survey about perceptions and attitudes towards learning. The data showed that 85% and 95% of headteachers believed that children at their school could complete primary Grade 2 literacy and numeracy assessments. Only 36% of headteachers believed children’s literacy was a ‘problem’ at their school.

While 94% of headteachers told researchers that they worried about children being promoted to the next grade without sufficient skills, 82% said that their focus is on finishing the curriculum on time. Most headteachers (88%) felt that they had enough materials to support children, but fewer than half perceived parents and community members as doing enough for children’s learning.

These figures imply that headteachers’ perceptions may be misaligned with, or overly optimistic about, actual learning levels in their schools. They also indicate that more needs to be done during pre-service and in-service training to enable teachers to understand their students’ learning. In particular, teachers should be equipped to assess children at an early stage in their primary school years, not least to identify those who need extra help.

Find out more

Wadmare, P., Nanda, M., Sabates, R., Sunder, N., & Wadhwa, W. (2022). Understanding the accuracy of teachers’ perceptions about low achieving learners in primary schools in rural India: An empirical analysis of alignments and misalignments. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 100198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2022.100198

Kobayashi, C. (2021). Understanding Head Teachers’ Responsibility towards Children’s Foundational Learning in Rural India: Focusing on their Perceptions, Attitudes, Barriers, and Actions [Apollo - University of Cambridge Repository]. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.80268

3

The parents who struggle to engage with their children’s education the most are often those with least.

Accountability from the Grassroots confirmed that the wealthier a household is, the more likely parents are to engage with their child’s education.

However, the gap was particularly pronounced above a certain economic threshold, beneath which, there were only minimal differences between how much parents and caregivers engaged with their child’s teachers, took an interest in their schoolwork or read to them at home. This indicates that lower-income communities as a whole should be the main beneficiaries of initiatives promoting engagement with learning.

According to existing research, the wealthier households are, the more involved parents tend to be in their children’s education. Similar patterns emerged from the study of rural communities in Uttar Pradesh.

Accountability from the Grassroots researchers collected information from 13,588 households. This included caregivers’ (90% parents) responses to five questions relating to engagement with their child’s education: (1) whether household members visited the child’s school; (2) whether they knew the name of their child’s teachers; (3) whether the child had learning support at home; (4) whether the respondent looked at their child’s books or schoolwork; and (5) whether someone at home read to the child or told them stories. Household wealth was measured using a 14-item asset index. Families were divided into five equal groups, ranging from the 20% poorest to the 20% wealthiest.

There was clear evidence that parents often care deeply about their children’s learning regardless of socioeconomic status. However, there was also a pronounced relationship between wealth and parental engagement, and a noticeable gap between the engagement of those who had most and those who had least.

For example: caregivers in the middle and “rich” quintiles were three and six percentage points more likely than those in the poorest quintile to check a child’s notebook, but those in the top (“richest”) quintile were 12 percentage points more likely to do so. The top 20% was also 16 percentage points more likely than the bottom 20% to help children with their studies.

Wealth could therefore be a yardstick for targeting support to increase parental involvement in education, but it should also be treated with caution. In general, wealth seems to influence parental involvement at the top of the scale, and below a certain economic threshold, parental involvement tends to be quite low by default. Since all the families in the Accountability from the Grassroots study were of relatively low socioeconomic status, targeting these groups at a community level, rather than separating them into wealthier and less wealthy families, may be an effective strategy. The link between wealth and engagement is also one of association, not causality. Therefore, targeting should be accompanied by supporting interventions such as the ones implemented by Pratham (PAHAL+), which increases parental and teachers’ commitments towards children’s learning.

Find out more

Cashman, L., Sabates, R., & Alcott, B. (2021). Parental involvement in low-achieving children’s learning: The role of household wealth in rural India. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101701

Cashman, L. (2023). Parental Involvement in Children’s Schooling and Learning in the School, Home and Community in Rural India. [Apollo - University of Cambridge Repository]. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.104153

UKFIET blog: Parental perceptions and parental involvement in children’s education in rural India: lessons for the current COVID-19 crisis.

4

Education evaluations should not only ask what works – they should also ask why and how.

Alongside the randomised controlled trial in 400 villages described above, the study also included detailed qualitative research to understand intervention uptake in four of those villages.

To select the villages for these case studies, the team employed a multi-stage sampling approach which combined ground-level input from key informants with baseline data from the RCT. This enabled them to develop a more nuanced selection of case study locations, combining the rigour of data from the RCT with in-depth understanding of key actors on the ground.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) provide valuable evidence about whether an intervention works but can overlook important details about the mechanisms governing success or failure. This research, therefore, also sought to explore not just if the PAHAL+ intervention worked, but also how and why it was effective. To do so, the researchers needed to select four sites for in-depth case studies from among the 200 villages reached by the PAHAL+ intervention.

The selection of the case study sites required a nuanced approach as relying on quantitative data alone to make this selection could have masked significant discrepancies in how effectively the intervention was implemented.

This was particularly the case given that local dynamics affected the implementation process. Anecdotal evidence revealed, for instance, that in some villages with low levels of youth and adult education, volunteer-led community classes were difficult to organise. In some communities, young people were often enlisted into domestic and income-generating activities, preventing them from attending study groups outside school hours.

To capture a more nuanced picture of how the intervention was being received on the ground, the researchers adopted a multi-stage sampling approach.

First, in a series of Focus Group Discussions, senior programme staff (“key informants”) helped to identify and then use a set of parameters to nominate two “responsive” and two “difficult” sites from each of the 15 rural administrative blocks in Sitapur district where PAHAL+ was being implemented. These selections were then refined using baseline data from the RCT. The final four villages were chosen to maximise the geographic spread and variations in teacher and parental awareness of children’s learning levels, as well as student enrolment and attendance, ensuring the sites were connected to the trends uncovered by the wider study.

This approach allowed the researchers to focus on responsive sites: three of the four were villages where progress was being made with PAHAL+, enabling the team to examine the conditions that were facilitating stronger school and community engagement. At the same time, including one “difficult” site allowed the researchers to examine the conditions and relationships due to which the programme was not able to achieve the stated goals.

From a research methods perspective, this project demonstrated ways in which large-scale RCTs can incorporate qualitative analysis to move beyond “what works” and explore why and how interventions succeed or fail. Combining multiple data sources – both qualitative and quantitative data – for sampling was essential to this fuller understanding of the dynamics at play. Relying solely on baseline data to select the case study sites would have excluded data on the process of intervention implementation, thus limiting any attempt to understand contextual differences which might contribute to its success.

Find out more

Ramanujan, P., Bhattacharjea, S., & Alcott, B. (2022). A Multi-Stage Approach to Qualitative Sampling within a Mixed Methods Evaluation: Some Reflections on Purpose and Process. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 36(3), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.71237

All images licensed for use by kind permission of the ASER Centre, India.